Welcome to Barstool Bits, a weekly short column meant to supplement the long-form essays that appear only once or twice a month from analogy magazine proper. You can opt out of Barstool Bits by clicking on Unsubscribe at the bottom of your email and toggling off this series. If, on the other hand, you’d like to read past Bits, click here.

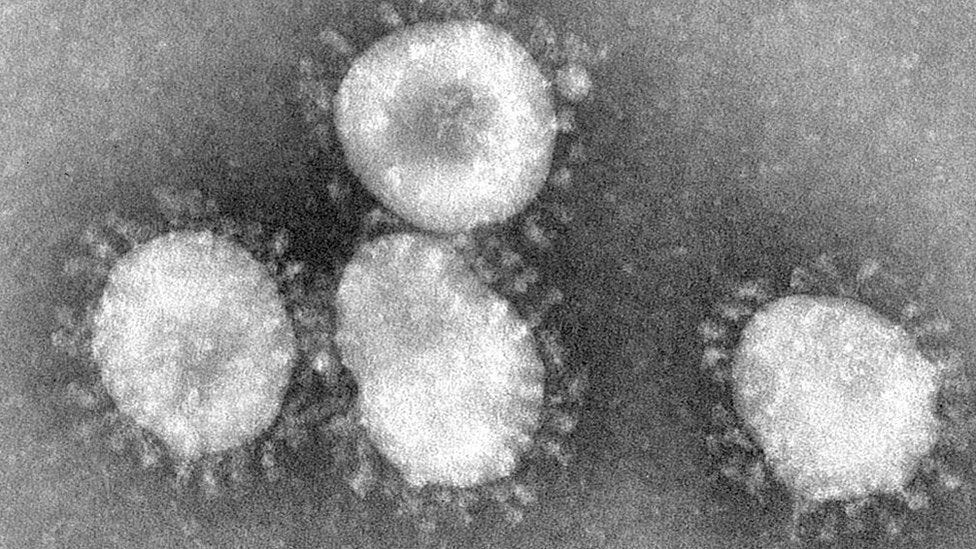

So I’m visiting a friend and she starts talking about one virus surfing on another, relaying this in all seriousness and presenting it as science. Before I know it, I’ve blurted out, “You realise no one’s actually ever seen a virus.” She was scandalised, as she ought to have been, of course, but not in a good way. She had a full-on attack of leftbrainitis and raised her voice, citing a litany of evidence all having to do with her having had virus x and y and z. I think she may have stamped her foot. Somehow the subject of artists’ renditions of viruses entered the conversation, and her son explained that, yeah, he was aware that the covid images weren’t real. He followed up by showing me an image on his phone of covid under an electron microscope.

I replied that one has to understand how electron microscopes work. You can’t witness living activity; it’s all processed and frozen, and so the impression you have of such an image can be misleading. Thing is, an image truly is worth a thousand words; while my brief response was just an argument, and no one has ever been convinced by an argument (well hardly anyone). In any event, the problem is that he could easily call up a picture of something I had claimed that no one had ever seen. (I’d like to see surfing viruses one day; it would likely explain a lot about how static images can be read into narrative structures.)

Having witnessed the most common research process practiced today, I think we can better understand what’s going on with the information/misinformation axis, and why it is so many people are convinced of and dedicated to unverified ideas; indeed, why it is they become believers in various notions about the world.

Essentially, the internet lends itself to confirmation bias. When you perform a search, it’s generally not merely to explore or truly browse; you do it to find more information about some subject or other. I don’t recall ever looking something up and getting a critique of the subject, unless it had been politicised or classified as “misinformation”—which means it was “fact checked” and represented in a biased manner, often out of context and misleading in its own right. That’s the essence of politics after all: to take a clearly decided stance on a subject, to represent one side of a discourse and lead a band of enthusiastic believers.

When it comes to science, however, or the search for knowledge, another approach is called for. True research requires three main, foundational practices: (1) researching the author or authors of any image or text, (2) seeking out primary sources, original documents (including images), and (3) seeking out critiques, refutations and counter claims. The internet, in its present form, discourages these avenues of discourse owing to bias-confirming algorithms, and the all-too-human propensity to be content with easy answers from authorities.

In this case, the search was for a microscope image of covid. “Seek and ye shall find!” Arguably, the electron microscope is not a microscope at all, and the fact that it is so called is misleading. The whole point of a microscope is to be able to directly observe minute phenomena. The electron microscope, however, introduces all manner of secondary phenomena and mediating technologies, and, therefore, provides only indirect observations. In other words, the phenomena observed are no longer themselves, but instead futzed with and contaminated by the processes inherent to the instrumentation. I encourage readers to look into the various forms of electron microscopy (and there are a lot of them!) to confirm what I’m saying here.

It gets worse. With the introduction of computer modelling, the images produced by these machines are taken up into narrative frames to render representations and animations of processes that exist only in theory and that no one has ever actually witnessed. By its own magic, however, the representations become seen. In effect, we can no longer say that no one has ever seen these minute phenomena. We must be very specific: “no one has directly observed such and such” and this qualification takes a lot of steam out of the argument.

The instrumentation enhances the same processes by which we see, goes the assumption; and this assumption flows logically from the fact that the device in question is called a “microscope.” While it is indeed a way of imaging at minute scales, a basic trouble arises from these minute scales being beyond actual illumination. Instead of light, electrons are used to render images. What does this mean? Essentially, that energy is focused on an object and refractions are registered to provide an image, much the way light behaves in the world when it hits our retinae. It’s a clever workaround except for all the contaminations introduced to provide a sample that can be imaged in this manner. Often resins and metals are introduced to samples, for instance. No doubt, these devices are excellent for observing certain kinds of phenomena and for helping produce fantastic new superconductors and maybe microchips, but this technology does not suit all samples equally. To be used correctly, the limitations of the device vis a vis the phenomenon in question must be appreciated.

Returning to the research problem at hand, ask Google to show you an un-enhanced microscope image of a virus and you will get just that—though all such images are technically enhanced. To find out enough about the image, however, you must chase it down, find the primary source, the research paper attached to it, consider the controls, the authors, their other work and affiliations, their critics and the critics of the subject under investigation. Only when you have completed these tasks can you say you’ve researched a topic. Simply googling for an image of covid or proof of global warming is not research.

If the internet is ever going to overcome its present divisive sense of information and truth, we, as a society, will have to come to the understanding that misinformation is generated by the notion that Truth is a kind of multiple choice quiz or a binary matter to which the answer must be 1 or 0. To remedy this problem, we need a new kind of search engine made for research rather than quick reference, one that renders an array of avenues for the three fundamentals listed above: (1) providing leads on authors, (2) leads on primary sources, and (3) critiques, refutations, and counter claims. The sensibility that would arise from such a search engine would radically change the public, political, and scientific perception of information and knowledge as right and wrong. It would turn to a dialogical rather than a monological approach. It would put folks on alert to the deficiency of over-confident claims, and the deficiencies of their own claims to having “researched” a subject. It would introduce a healthy scepticism to a discourse that has been growing ever more divisive by the day.

I direct those interested in learning more on the subject of electron microscopy and virus imaging to view Dr. Sam Bailey’s video Electron Microscopy and Unidentified “Viral” Objects. She shares some images and discusses the main issues at play when these visual renderings are engineered and interpreted. The chief problem is that the particles we call “viruses” still haven’t been proven to behave like parasites, and so even if one identifies a biological particle associated with a specific illness, it is unclear what the role of that particle is, simply because no one has, in fact, witnessed the process of viral infection, and replication through hijacking living cells. For all we know, the particles found in electron microscopy are a kind of cellular debris—i.e. the way a cell breaks down when subjected to a given corruptive agent—or the arrival of other biological agents meant to clear the dead cell.

This subject is probably even more controversial than global warming. It is a wonder that such is the case if only because of the inconsistencies of virology and immunology. We seem perfectly happy with the falsifications we have all witnessed with regard to the idea of viral transmission as cause of illness, since we’ve all been privy to instances in which no illness results from proximity, or in which a healthy individual is deemed to be a “carrier”—an unclean person, as it were. At this stage of the game, it’s essentially understood that we are all carriers, which ought to water down the whole paradigm. Calling carriers “infected” is among the more dubious notions floating around. And the whole thing would be silly were it not for the lockdowns and UN Pandemic Preparedness Treaty hanging over our heads like a sword of Damocles.

Asa Boxer’s poetry has garnered several prizes and is included in various anthologies around the world. His books are The Mechanical Bird (Signal, 2007), Skullduggery (Signal, 2011), Friar Biard’s Primer to the New World (Frog Hollow Press, 2013), Etymologies (Anstruther Press, 2016), Field Notes from the Undead (Interludes Press, 2018) and The Narrow Cabinet: A Zombie Chronicle (Guernica, 2022). Boxer is also the founder and editor of analogy magazine.

One of the main vectors of trouble is that science teachers and profs discourage deep questioning like how did Newton derive G? or how do we know viruses are real? etc. So it will take gumption for a truly inquisitive student to make it through the system.

"This subject is probably even more controversial than global warming."

Aye, I'm afraid so. I find it very entertaining and valiant when you 'fight positivism with positivism', but it's also a little frustrating for me for entirely pragmatic reasons - I want to engage with you in this arena, but the philosophical topics are too huge to approach from a standing start. I'd need a well-made conceptual skeleton key to get to where the discussion would be fruitful and I don't have one right now.

In brief, however, the sciences are riddled with entirely conceptual entities... you don't need to go for virus, electron is fine as an exemplar (much less controversial). I think it's the best example because despite the impossibility of observing an electron, we would not ditch the electron without another model that supplanted it and plugged the theoretical gap. This is also how I feel about the virus as a conceptual entity - the contagion model is badly broken (the challenge trials research are fascinating in this regard!) but the virus concept does plenty of work elsewhere too e.g. I don't know how to explain the Antarctic cod's glycoprotein without it. I'm willing to entertain all options... but we're dealing with tightly interwoven webs of concepts and complex questions about epistemology here.

I very much like your idea about a new kind of search engine... I don't think the commercial forces exist to get this made, alas.

Please forgive this 'glancing blow' - and also consider it a raincheck for a future discussion on this! I'll need to craft some tools to make our hypothetical future conversation worthwhile.

With unlimited love,

Chris.