Welcome to Barstool Bits, a weekly short column meant to supplement the long-form essays that appear only two or three times a month from analogy magazine proper. You can opt out of Barstool Bits by clicking on Unsubscribe at the bottom of your email and toggling off this series. If, on the other hand, you’d like to read past Bits, click here.

In literary studies we examine both mythoi and typoi. Mythoi are typical narrative structures, and typoi are the archetypal characters that drive the plot. The romantic hero and the questing hero, for instance, must contend with blocking figures like the jealous brother, the knave, or false friend who secretly undermines the hero’s schemes, or the old man (father or pimp) who stands in the way of fulfilment with the beloved. Meanwhile helping-figures like the wise man or woman and the loyal servant (or true friend) aid the hero in his quest.

As literary critic Northrop Frye lays out in his monumental Anatomy of Criticism, the archetypal mythoi may be plotted on a pie chart invoking the four seasons or the path of the sun: where the quest-romance (not to be confused with erotic romance) finds the hero at noon or midsummer, at the height of his powers fighting monsters and saving maidens in distress; the tragedy finds the hero at twilight, or autumn, seeking to right a perceived wrong but seduced into error, resulting in his fall from grace, mass death and the destruction of a corrupt community; the satire follows the hero into the wintry night region or underworld of senseless rules and an inverted world gone mad where he is impotent to bring about change; and the comedy is the redemption of that sick society as the hero emerges from the darkness into the dawn and springtime, triumphant, reborn and emancipated (often sexually) along with his community.

Considered from the perspective of this model, the mythos of science follows the typical structure of a comedy, as do the Christ and Buddha stories. A satirical period sustained and suffered through in an underworld is always implicit in comedy. Comic heroes find their society afflicted with arbitrary and oppressive rules upheld by ridiculous characters. Often the action of the tale is precipitated by such rules and the foolish characters who uphold them.

Likewise the science mythos is all about emerging from a dark period of ignorance and dogma, overthrowing the arbitrary and undeserved power of the Church and clergy that was oppressive to human progress and freedom. Through the application of the scientific method and objective reasoning, science raised humanity from a benighted state into an enlightened one; thereby the greater community—formerly the Church or temple—is redeemed into a secular society under one universal institution committed to objectivity and progress. In the process, the fools and corrupt former leaders are exposed, publicly lambasted (or otherwise persecuted) and ejected, thereby cleansing the community and making room for the new dispensation.

So the mythoi and typoi are more than just works of the imagination without connection to reality. Nor are they pure whimsy and jumbled dreamscapes. Instead, archetypal stories and characters mimic political, social and emotional expression. I am getting at the heart of the confusion among new atheists and subscribers to TheScience™ who do not understand the relevance of stories and storytelling to their lives, and to what degree their own perceptions are moulded by archetypal “fictions.” For as I’ve shown in previous articles, the driving mythos of Science as a redeeming hero (a Christ or Buddha figure) driving out the aberrations of a litigious and barbaric hierarchy and a dogmatic scholasticism, is only partly true. A scientific zeitgeist did indeed help displace the former hierarchy which had become oppressive, but it could not achieve this alone. Humanism, pluralism and republicanism were equally necessary forces. Moreover, science emerged organically through the persistent efforts of deeply spiritual seekers after Truth and wisdom.

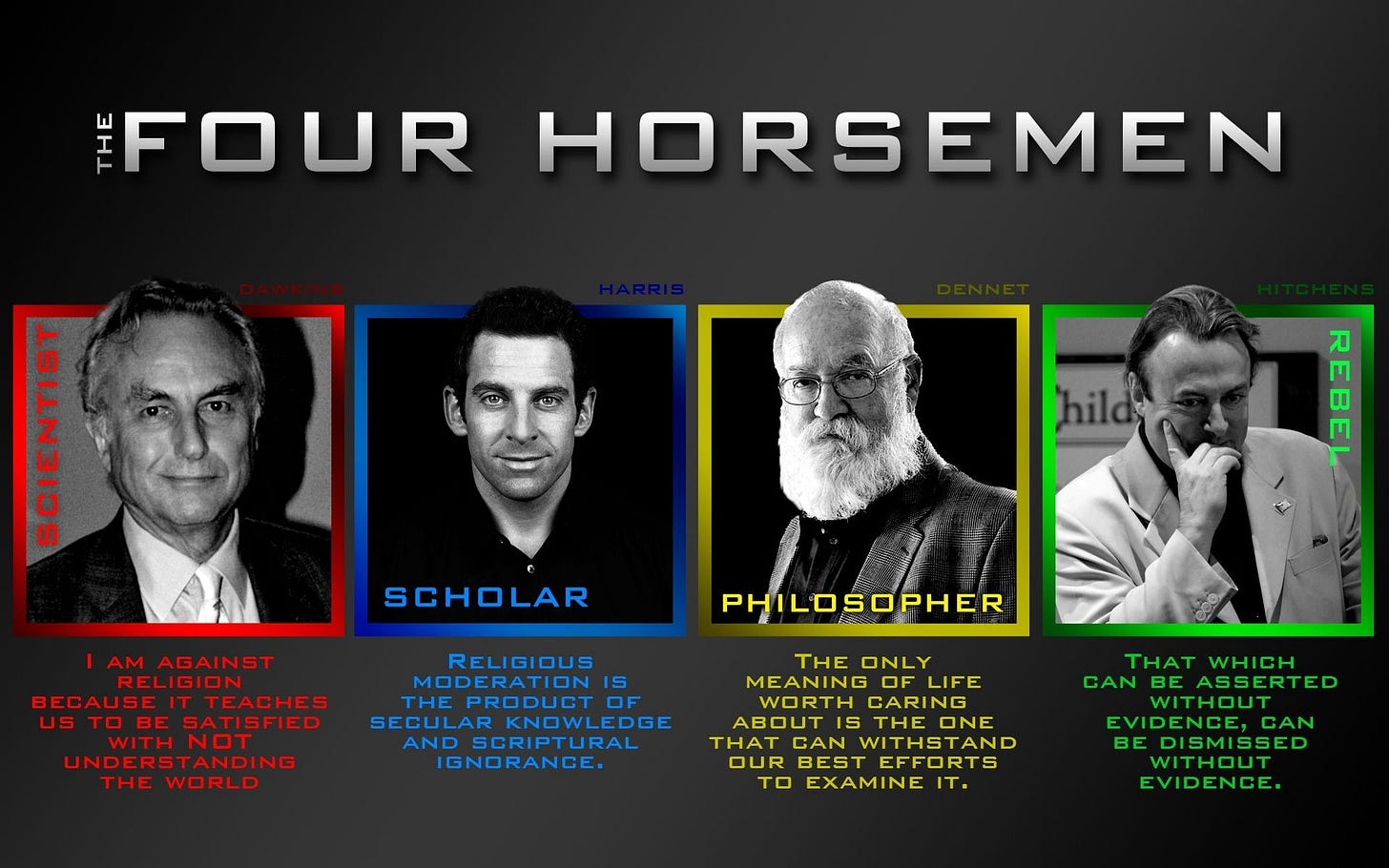

Ironically—and likely because they have not read enough and do not understand how stories work—new atheists have taken up the roles of those idiotic blocking figures typical to satire and comedy. As a formerly radical position became institutionalised, fanatical atheists took up positions of authority in the growing institution and transformed into staunchly orthodox typoi—clones of the predecessors they so love to mock. Instead of comedic heroes, the new atheists slipped into the role of those satirical, rule-heavy authorities wielding oppressive power. (See my articles on Neil deGrasse Tyson, Michael Shermer, TalkOrigins Archive, and Sam Harris.) Our present day is thus a satirical period in which helpless protagonists rail against the prevailing paradigm (TheScience™) without hope of achieving anything, except earning a reputation for tilting at windmills.

Asa Boxer’s poetry has garnered several prizes and is included in various anthologies around the world. His books are The Mechanical Bird (Signal, 2007), Skullduggery (Signal, 2011), Friar Biard’s Primer to the New World (Frog Hollow Press, 2013), Etymologies (Anstruther Press, 2016), Field Notes from the Undead (Interludes Press, 2018), and The Narrow Cabinet: A Zombie Chronicle (Guernica, 2022). Boxer is also a founder of and editor at analogy magazine.

I like how this essay illustrates a way of seeing that gives stories a central place in consciousness. Without stories, how can we ever become whole persons, body and mind, while analytic science divides us into an assembly of parts provisionally joined? This abstraction of materialist thinking, by dividing body from mind, seems to deny us the physical basis for a sympathy that could join us more intimately to one another. We see the destructiveness of this mental frame everywhere. Yeats warns against such extreme mentalization of thought in his poem "A Prayer for Old Age": "God protect me from the thoughts men think/ In the mind alone."