Welcome to Barstool Bits, a weekly short column meant to supplement the long-form essays that appear only once or twice a month from analogy magazine proper. You can opt out of Barstool Bits by clicking on Unsubscribe at the bottom of your email and toggling off this series. If, on the other hand, you’d like to read past Bits, click here.

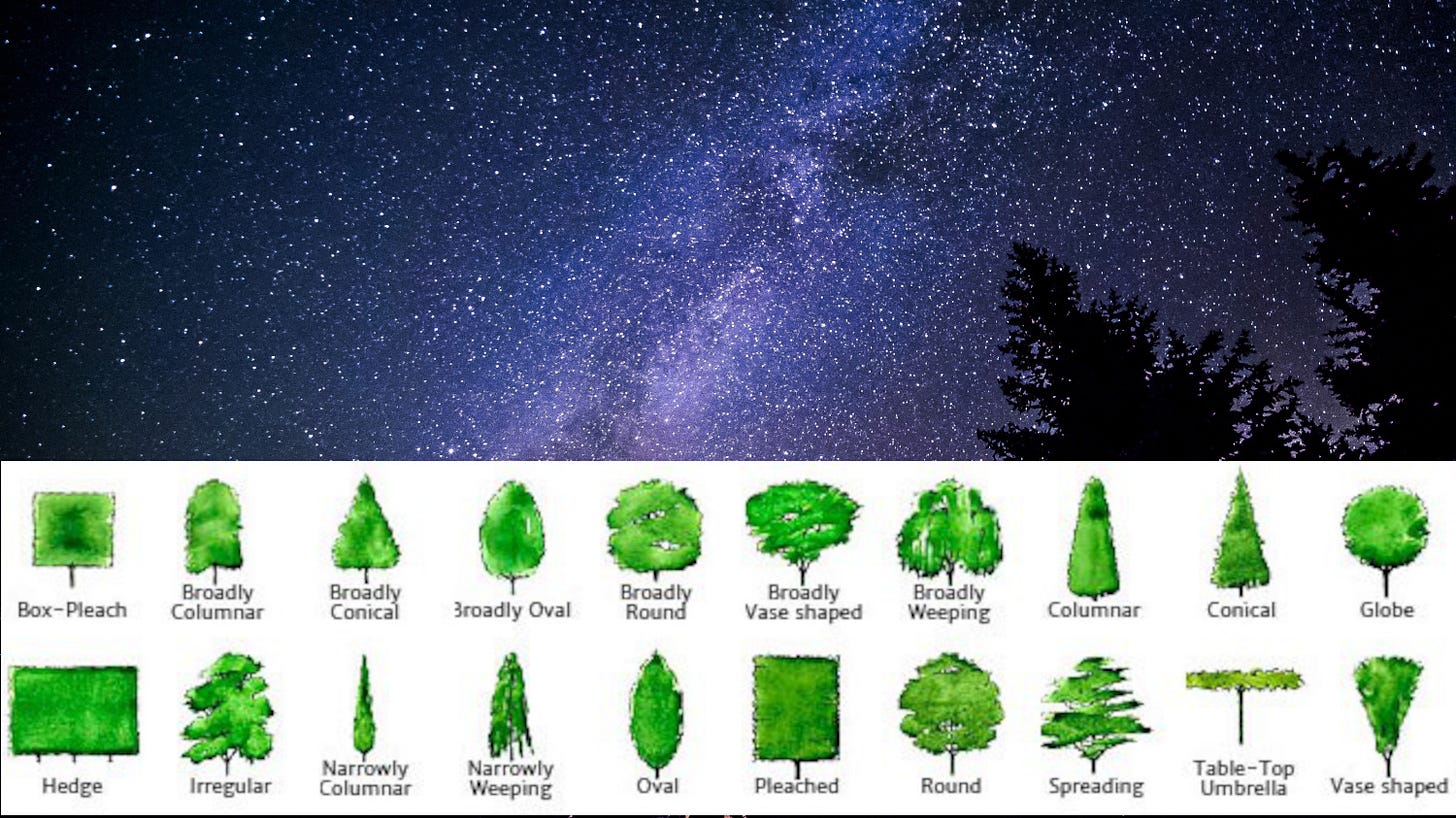

When I look at the night sky, I see constellations. Since taking a course on plant identification, I see tree shapes according to the tree-shape chart above. The more I learn, the more conventionalised my perceptions become. I am educated into a kind of stupor. Things are what we call them and that’s that. There’s no denying the charts and tables, no denying the stats. Questioning such things is either stupid or disingenuous, goes the reasoning. It would seem that this sort of commitment to our models has been troubling me for a long while. I wrote the following poem sometime before launching analogy magazine, before the lockdowns, while still living in Montreal.

Release

I climb like I’m climbing out of my skin, climbing out of my own hair

as I climb out of traffic, away from thundering machinery.

I climb past joggers and cyclists snug in their spandex.

I bolt through woods, bound rocks, teeter across mud-locked logs.

The fine drizzle sizzling over the ground is the tearing sound

as I come loose like a stone dislodged from peach-flesh.

Once out of the pollutiosphere, even the bird chatter is thin.

I inspect a feather, an acorn, a vacant web, and each time,

kaleidoscopically, the whole world pivots on the axis of a new design.

What is a park in darkness or in rain when it no longer serves?

When the purpose departs a field, an old wheel, a clawfoot tub,

what does it become—when it slips the syntax of our hands?

I pick a button from the grass; the turf bares its chest to the sky.

Let go the strings of constellations, the stars fly back to themselves.I mention that this piece predates analogy magazine by a significant period because it strikes me that it anticipated the premise of this conceptual space. Clearly, the idea that our models obscure the phenomena had been knocking around in my head for quite some time.

I’m on the lookout for new ways to communicate this notion, since it’s by no means obvious until one grasps it; and then, of course, one sees it everywhere. My intuition is that equipped with this new and improved Windex, one may rub away a little circle of clarity amid the greasy film of education smudged over our windows on the world. This window metaphor predates “Release.” The following poem is from a chapbook called Etymologies (2016).

Speculation Looking like one who wears his eyes with crow’s feet, likewise, I looked around her like a tracker for signs of passage and telling scat. Entirely absorbed in looking, like a traveller looking down the road; rapt as a child peering through a window; I looked forward beyond the reach of my eyes with images already in mind, till I could no longer look her in the eye and had to look instead inside, looking at the world through a film of the world: the shadow of my desire flickering against the ghost of being.

When Plato famously suggested, through his allegory of the cave, that our perceptions are shadows rather than realities, he was getting at the same trouble. I’m not claiming to be an innovator. But I do think our culture has lost sight of this fundamental truth. We’ve become particularly good at obfuscating phenomena with conventional, institutionally approved, models. Worse, whatever is at variance with these conventions is being deemed “misinformation.”

Unfortunately, these considerations strike too many in our society as “metaphysical,” which there’s no denying; but the word metaphysical also strikes folks as too highfalutin to be of practical use. Thing is, we’re at an infection point, culturally and historically. Our neglect of the metaphysical substrate to our reasoning is having real-world impacts: from pandemic response to climate change policy to freedom of speech and censorship and even to the ethics of our private thoughts and conversations.

Perhaps the worst of it is our emotional wellbeing. According to the mechanical-accidentalist view, there is no value to suffering. Why should we have to feel so much emotional pain that we cry, when, instead, we can take some approved pharmaceutical that numbs us out? Why feel pangs of guilt or shame and the accompanying anxiety when we can pop a pill instead and carry on like nothing happened? It’s a recipe for psychopathy.

I’m reminded here of a wonderful video on the subject of how lobster’s grow. Essentially, the shell has to get so constrictive and difficult to live in that the lobster must work to remove the old housing. The world’s reactions to us and our reactions to the world absolutely must cause us suffering or we won’t grow. Instead, we remain stuck in a narcissistic state, a state defined by being unable to empathise or connect in any meaningful way. It doesn’t get more practical than that.

But that’s all inside, mushy stuff. What about the things that matter, like vaccines and carbon emissions? We’ve all seen the stats on the effectiveness of vaccines, right? They cured smallpox and polio. And what’s more, when folks refuse them, we get resurgences of these diseases. Stats don’t lie. Similarly, CO2 is a greenhouse gas that causes global warming. Just look at Venus with it’s high CO2 atmosphere and temperatures above 450°C! Numbers don’t lie.

I have no intention of entering these debates today. What I’m after is how these perceptions become conventional, and once in the conventional bloodstream, as it were, they become fixed. I have had plenty of in-depth conversations with folks who tell me they are fundamentally sceptical and that science is always uncertain, only to have them declare at some emotional moment that they “believe in the science.” The emotional moment is invariably a symptom of leftbrainitis, as the left brain must be right, and how can it be right and uncertain at the same time? So it recruits the notion of believing in a certain paradigm, and remains oddly blind to its own manoeuvres.

The remedy to this predicament is poetry, especially anything that’s truly surprising in its formulations—poems that make you see the world afresh, poems from which you turn away and the world is no longer quite the same, poems that break one’s conventional and cliched views. Ultimately, the goal, as I see it, is to escape these paradigm lockdowns. I want to be able to look at the night sky and see the stars on their own terms, if that’s a thing—or at the very least, on new terms. I want to be able to look at trees and just see that tangle of trunks and limbs. With that in mind, I’ll leave you with one more poem:

Natural Resistance

How the trees resist the winds, are shaped by them,

and in turn give them voice and form. Shakespeares all,

they lend themselves to and resist the tastes and penchants

that would twist them fashionably one way or another.

They stand starkly engaged in their magic:

ponderous, monumental, waving their gnarled wands

clutching at the sky as though channelling lightening,

thrust deep in the plasma of the heavens,

or like shivering neurons relaying the feelings

of sky to earth and back, the pillars of reality.

What happy mystery how they forever draw my gaze

with always some renewed fascination,

as though through their patient calling forth to life

—from bronze-scalloped bud to green leaf,

to prestidigitous clutch of petals held in the shape of a flame,

a drop, a hand bringing its fingers to an essential point

before opening to a blossom flushed and fragrant,

to fruit-locked seeds and stones packed with the flavours of perpetuity

to abject loss and total, skeletal grief, and back to bud and leaf—

as though through this endless cycle, they have come to know

to the core and convey to the heart of one who stops

a moment, arrested by the cathedral of their limbs,

the ever-novel ways in which a single thing may be forever recast.

How they reach forth always, holding out their offerings.

More than ever—this bitter spring, when I have lost all touch

with the earth—I need their wooden gestures. Today,

the sun shines brighter, it seems, than it’s shone

in I don’t know how long, but surely longer than a season;

as if the terrestrial precession has brought us,

this spring, closer to the celestial fire than any spring

I can remember in a good many rounds of this

pugilistic match we count in years.

All we’ve been stashing under the snow is out,

seeping from the receding frost-line, wafting

their terrible odours like an ancient penitent in ash

and sackcloth crying out in guilt and shame,

for all this fishy mortality, the coiled peels of corruption,

the festering inkblots of mildew brown and incarnadine

afflicting the waste while the icy remains of snow

unconsciously fidget at fringes of lace

where the grass of last summer shows, slick

and matted as a newborn, the shape-shifting snow

everywhere revealing in its own way a lost world,

sopping and indefinite knits, vestiges of things lived-in,

hats, gloves, scarves, now manky, mangled husks,

ragged corpses, untouchable castoffs, the remnants

of shady intercourse trammelled and crushed

beyond recognition by albino elephant feet of snow;

the snow now turned artisan, making do with what’s left

of itself, drawing fanciful maps with filigreed boots and fjords,

and glazed-over flats, in desperate denial of the advance

of a new season, spiked in reluctant retreat

along its last-ditch crystal chains, still heaped

behind chevaux de frise. The shabby bark of a honey locust

hangs loose, patches are torn from the trunk of another.

Surely these know what it means to be separated from themselves,

pulled at by starving teeth or by the carefree hand

of a passing drunk. How they resist even the gentrification

of their space, the anthropocene scheme that plots them

at polite distances, the violence done their dramatic,

passionate limbs that they may be rendered picturesque,

safe according to the standardizing eye of the insurance underwriter.

And yet, see how one swings its hip dangerously out of line,

dancing at a pace that mocks the rhythm of human designs.Asa Boxer’s poetry has garnered several prizes and is included in various anthologies around the world. His books are The Mechanical Bird (Signal, 2007), Skullduggery (Signal, 2011), Friar Biard’s Primer to the New World (Frog Hollow Press, 2013), Etymologies (Anstruther Press, 2016), Field Notes from the Undead (Interludes Press, 2018) and The Narrow Cabinet: A Zombie Chronicle (Guernica, 2022). Boxer is also the founder and editor of analogy magazine.

Skimmed this yesterday, but still want to give it a proper reading when I get a chance... Great to read poetry and philosophy together!

I loved it, just the first time through, and look forward to coming back to your essay. This way you have of making the point and then inserting one of your poems is very effective for me, and when I reread I see more in the point and in the poem. I have been immersed in books about men who go into the wilderness, hermits of various kinds. One thing common to stories about or by them is that the gesture of climbing the mountain, or walking deep into the woods, removes what I'll call the cultural glasses, not just preconceptions but pre-experiences, so to speak, that filter what they see. When, once in a while, I get to a dark place, a spot where indirect light does not fade the sky, I am thrilled at what I see. And I am thrilled too by amazing pictures from cameras shooting through space. I take your post as a reminder that I can ditch the cultural glasses even when I am sitting in my office or living room. I don't have to see things the way I habitually see them. I've been trained in ways to see things. Pretty soon, as you say, what stands out is the habit, not the object of the gaze, the apparatus, not the thing seen. Thanks for the reminder to look for myself--in two senses, too.