Manifold Perception

So how is it that secularism is slipping away from us and being replaced by orthodox scientism? No doubt, there are many factors, including personal and corporate greed, pharmaceutical capture of public health institutions and the news media, aided by public ignorance of the depth and pervasiveness of this corruption. This study, however, must leave these and other equally relevant issues aside to focus on one significant crux: our cultural attitudes toward science as final revelation, and the erosion of the cultural conditions that give rise to creative, analogical thinking. This article explores the central role of pluralism in the formation of the philosophical, truly scientific mindset. Essentially, there can be no innovative, analogical reasoning without an array of cultural narratives to compare. Once a given worldview or paradigm takes total command of a culture, creative thought dies, since—as noted in my essay, “Scientism Subverts Secular Society”—such a culture perceives as illegitimate any practices unsanctioned by its ideology. Those who dare propose new insights are deemed heretics, or in today’s terms, deniers and denialists.

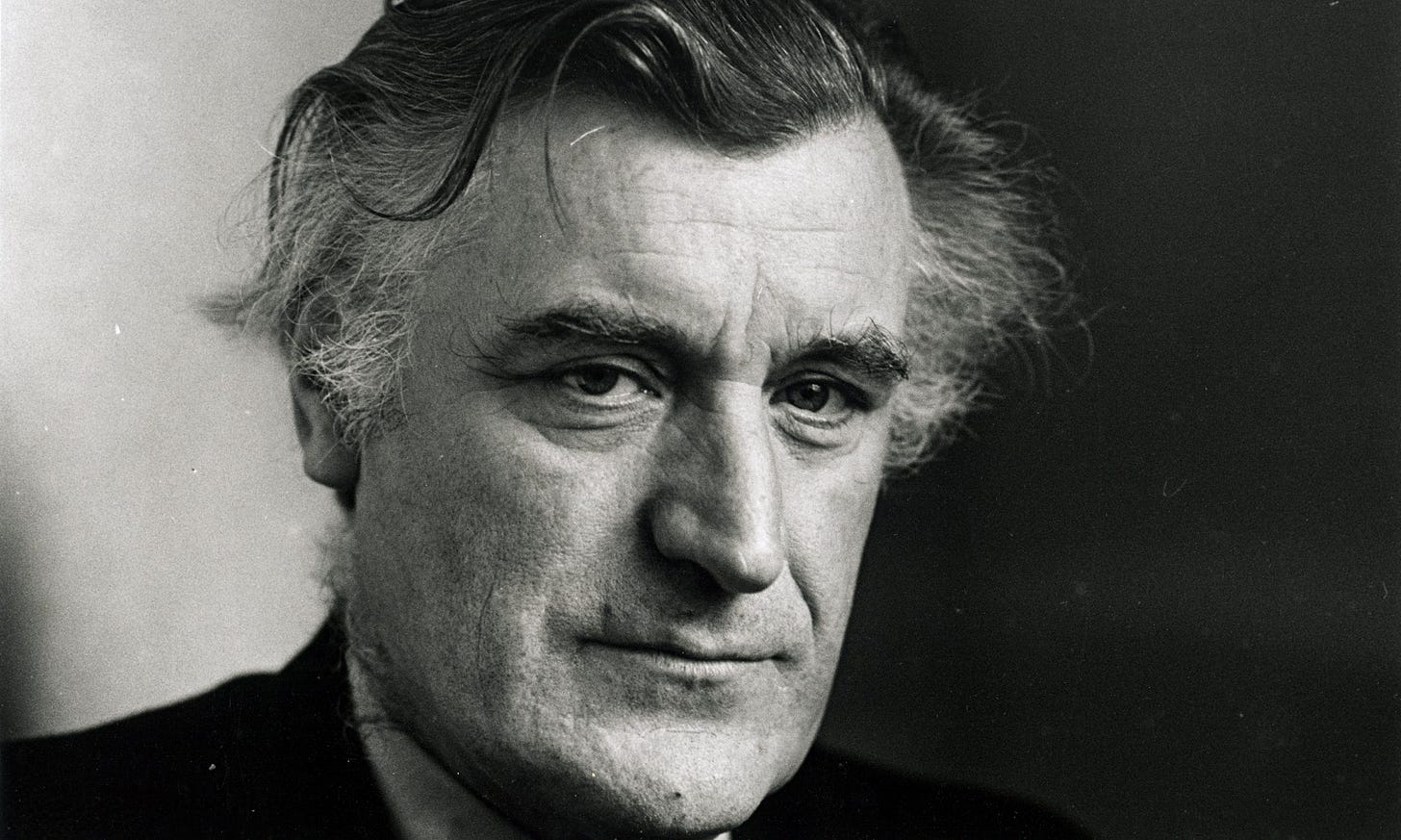

In “Myth and Education,” Ted Hughes—poet laureate of England from 1984 until his death in 1998—wonders about the origins of philosophy and the scientific method. “What was so special about early Greece?”—he asks:

The various peoples of Greece had created their own religions and mythologies, more or less related but with differences. Further abroad, other nations had created theirs, again often borrowing from common sources, but evolving separate systems, sometimes gigantic systems. Those supernatural seeming dreams, full of conflict and authority and unearthly states of feeling, were projections of man’s inner and outer world. They developed their ritual, their dogma, their hierarchy of spiritual values in a particular way in each separated group. Then at the beginning of the first millennium they began to converge, by one means or another, on Greece. They came from Africa via Egypt, from Asia via Persia and the Middle East, from Europe and from all the shores of the Mediterranean. Meeting in Greece, they mingled with those rising from the soil of Greece itself. Wherever two cultures with their religious ideas are brought sharply together, there is an inner explosion. Greece had become the battleground of the religious and mythological inspirations of much of the archaic world. The conflict was severe, and the effort to find solutions and make peace among all those contradictory elements was correspondingly great. And the heroes of the struggle were those early philosophers. The struggle created them, it opened the depths of spirit and imagination to them, and they made sense of it. What was religious passion in the religions became in them a special sense of the holiness and seriousness of existence. What was obscure symbolic mystery in the mythologies became in them a bright, manifold perception of universal and human truths.1

In other words, it was the convergence of many myths, many stories, many conceptions of the universe and humanity’s place in it that brought about the philosophical impulse to consider things more and more abstractly, more and more in conceptual and analogical terms. When one ponders, even today, the variety of belief systems at play, one feels compelled to conclude that either (a) the one we possess is the only true truth, or (b) that there is no truth, or (c) that there is some truth to all of them. Rejecting both exceptionalism and nihilistic relativism, one tends toward (c), mining for truth the areas where various perspectives converge.

Xenophanes of Colophon (c. late 6th, early 5th century BCE) was a poet-philosopher who turned a critical eye on the Homeric gods and their less than divine natures. Feeling a mismatch between their behaviour and the ethics of his society, he looked around at the wider world of which Greece had become aware, and noted an anthropomorphism that struck him as absurd:

But mortals suppose that gods are born, wear their own clothes and have a voice and body. Ethiopians say that their gods are snub-nosed and black; Thracians that theirs are blue-eyed and red-haired.

Perceiving this plethora of gods and goddesses, and considering how the various cults and clergies of his time espoused moral virtues and devotion to these deities, Xenophanes distilled a conception of divinity worthy of worship: one single God that encompassed them all while at once analogically standing for an ideal beyond the human:

One god greatest among gods and men, not at all like mortals in body or in thought.

Monotheism is a frameshift not credited enough. When the Biblical Abram took up an axe and destroyed the idols in his father’s shop, placing the axe in the hands of the chief god, and in answer to his father’s inquiry as to what had happened, claimed that the chief god had smashed the rest, he was—much like Xenophanes—ridiculing the naive materialist fallacy of conflating the material form with the idea. I cannot underscore this amazing change in perspective enough. We’re talking about a recognition fundamental to philosophical and rational thought, the distinction between our inner and outer worlds, between the material and the conceptual.

Meanwhile, the monotheistic God is still not properly understood because that distinction between material and conceptual has proven one of the most difficult for humanity to entertain. The first two commandments are all about this problem. Thou shalt have no other gods before me, and Thou shalt make no graven images are instructions intended to prevent any sort of mediation between the spiritual seeker and God because the monotheistic God is an abstract concept and not to be confused with a material thing or person. Monotheism is about the continuum of being; and it hopes to put the individual into resonance with creation. But always the materialist impulse intervenes, always that need for a material signifier that is analogically put for the abstraction. The stand in, however, is not to be confused with the subject for which it stands in. Most of our social confusion stems from this trouble distinguishing between the signifier and the signified. Logicians of metaphysics and language call this the distinction between de dicto and de re, between the thing stated (or represented) and the thing itself.

No doubt, the recidivism we’re witnessing in the sciences is ultimately to be lain at the feet of our education system, which is failing to train the imagination. This is Hughes’s insight. At the beginning of “Myth and Education,” he asks why it was that Plato, in The Republic, advocated teaching children the myths.2 If the ideal republic exiled the poets, then why raise kids on their works? Children could easily be trained on mathematics and logic alone. Why risk corrupting their minds with the absurd tales of supernatural beings who are anything but exemplars of ethical behaviour? Why teach them lies? This is a question we’re seeing posed again by New Atheists like Sam Harris.

“The story itself is an acquisition, a kind of wealth,” Hughes tells us. “We only have to imagine for a moment an individual who knows nothing of it at all.” Such a person would be alienated from our culture, would find himself “outside our society.”

Consider the conditions that gave rise to the philosophers of ancient Greece. There was something about the convergence of stories there that provided the ideal matrix for philosophical foment. For secularism to emerge, we require both pluralism and the freedom to bring the analogical mind to bear. As soon as there is only one way, the analogical mind dies and creative evolution, true innovation, hits a wall. Nature abhors such oppression and will always find a way to surmount and overturn paradigms that claim a final revelation. The purpose of raising children on stories and myths is to recreate the conditions of ancient Greece in their minds, so that they can have access to that fertile Ur-ground that produces philosophy and secular culture.

That’s it in a nutshell. But Hughes’s reasoning probes far deeper:

A child takes possession of a story as what might be called a unit of imagination. A story which engages, say, earth and the underworld is a unit correspondingly flexible. It contains not merely the space and in some form or other the contents of those two places; it reconciles their contradictions in a workable fashion and holds open the way between them. The child can re-enter the story at will, look around him, find all those things and consider them at his leisure. In attending to the world of such a story there is the beginning of imaginative and mental control. There is the beginning of a form of contemplation. And to begin with, each story is separate from every other story. Each unit of imagination is like a whole separate imagination, no matter how many the head holds.

If the story is learned well, so that all its parts can be seen at a glance, as if we looked through a window into it, then that story has become like the complicated hinterland of a single word. It has become a word. Any fragment of the story serves as the ‘word’ by which the whole story’s electrical circuit is switched into consciousness, and all its light and power brought to bear. As a rather extreme example, take the story of Christ. No matter what point of that story we touch, the whole story hits us. If we mention the Nativity, or the miracle of loaves and fishes, or Lazarus, or the Crucifixion, the voltage and inner brightness of the whole story is instantly there. A single word of reference is enough — just as you need to touch a power-line with only one finger.3

“The story itself is an acquisition, a kind of wealth,” Hughes tells us. “We only have to imagine for a moment an individual who knows nothing of it at all.” Such a person would be alienated from our culture, would find himself “outside our society.” Hughes explains:

To follow the meanings behind the one word Crucifixion would take us through most of European history, and much of Roman and Middle Eastern too. It would take us into every corner of our private life. . .Openings of spiritual experience, a dedication to final realities which might well stop us dead in our tracks and demand of us personally a sacrifice which we could never otherwise have conceived. . .Those things have been raised out of chaos and brought into our ken by the story in a word. The word holds them all there, like a constellation, floating and shining.4

The totality of stories we read, hear and learn are “an acquisition” which constitute our cultural heritage. But that’s not all. “Imagine,” Hughes proposes, “hearing somewhere in the middle of a poem being recited, the phrase ‘The Crucifixion of Hitler’ ”:

The word ‘Hitler’ is as much of a hieroglyph as the word ‘Crucifixion’. Individually, those two words bear the consciousness of much of our civilization. But they are meaningless hieroglyphs, unless the stories behind the words are known. We could almost say it is only by possessing these stories that we possess that consciousness. And in those who possess both stories, the collision of those two words, in that phrase, cannot fail to detonate a psychic depth-charge. . .All our static and maybe dormant understanding of good and evil and what opens beyond good and evil is shocked into activity. . .

. . .

The stories have gathered up huge charges of reality, and illuminated us with them, and given us their energy, just as those colliding worlds in early Greece roused the philosophers and poets.5

So it’s not cyphers and words alone, it’s not abstract concepts and mathematical precepts and data points alone, it’s the stories we devise from those constellations, and the interactions of those stories that enlighten, that enable those novel frameshifts that are the hallmark of our creative evolution. What the two stories of Christ and Hitler “show very clearly is how stories think for themselves, once we know them”:

They not only attract and light up everything relevant in our own experience, they are also in continual private meditation, as it were, on their own implications. They are little factories of understanding. New revelations of meaning open out of their images and patterns continually, stirred into reach by our own growth and changing circumstances.

Then at a certain point in our lives, they begin to combine. What happened forcibly between Hitler and the Crucifixion in that phrase, begins to happen naturally. The head that holds many stories becomes a small early Greece.

It does not matter, either, how old the stories are. Stories are old the way human biology is old. No matter how much they have produced in the past in the way of fruitful inspirations, they are never exhausted. . .There is little doubt that, if the world lasts, pretty soon someone will come along and understand the story as if for the first time. He will look back and see two thousand years of somnolent fumbling with the theme. Out of that, and the collision of other things, he will produce, very likely, something totally new and overwhelming, some whole new direction for human life.6

The analogical mind understands that our cognitive apparatus depends on stories and that our stories “are never exhausted.” New analogical parallels are always presenting themselves. With each new technology, humanity has access to new metaphors, opening up new perspectives. The industrial revolution inspired the Enlightenment thinker Julien Offray de La Mettrie to look back at Rene Descartes’ idea of the animal machine and write L’homme Machine, looking at human biology as a machine. This analogical move represented a frameshift away from Galenic medicine and the theory of humours toward something new. Doubtless, newer perspectives taken from newer innovations like electricity and electronics will evolve and displace our present perspective.

“It does not matter, either, how old the stories are. Stories are old the way human biology is old. No matter how much they have produced in the past in the way of fruitful inspirations, they are never exhausted” - Ted Hughes

Stories & Laws

In his study Missing Link: The Evolution of Metaphor and the Metaphor of Evolution, poet and literary scholar Jeffery Donaldson remarks, “Religionists and scientists may have a hard time getting on the same page of late, but one thing they do have in common is a reluctance to be considered story-tellers”.7 This fallacy is the source of the materialist recidivism to which I keep pointing. Fact thumpers are no different from Bible thumpers. They both believe they are in possession of an ultimate and final revelation. The analogical mind understands, however, that such dogmatism means to shut down our creative evolution. A fact thumper may, for instance (and this is a common example), invoke the undeniable action of gravity on Earth. Beyond the notion that most objects have a tendency to fall, and that when they do fall, there’s a mathematical formula concerning their rate of acceleration, the law in question is not quite what the fact thumper makes it out to be. So many factors intervene that even the basic formula requires adjusting when outside its ideal frame. Friction, wind currents and the shape of the falling object require consideration. In addition qualities like temperature and the medium through which the object falls add further factors, possibly involving displacement and buoyancy. For the said fact to have any relation to reality, so many circumstances must align that it can hardly be called a fact; soon enough we’re looking at a much diminished heuristic or useful guideline to help provide rough estimates of material behaviour within a limited frame. Newton’s Universal Law of Gravitation nearly satisfies the notion of a fact, but in what sense it is a Law is a question of its frame of reference. It is of course a mathematical law, a question of geometrical relationships in relation to quantities of mass. Expressed in mathematical terms, one is impressed by the metaphysical implications, and it is to these implications that we apply the notion of a Law.

I must admit to being seduced by this alignment as much as anyone else. However, we must not allow that seduction to occlude the possibility that the applicability and productivity of the heuristic—i.e. the fact that it works—is incidental. History is full of discarded heuristics that were productive. The Ptolemaic system, for instance, was completely false and yet reliable enough mathematically to predict eclipses and make calendars. The Big Bang is far worse because it makes of a tenuous claim a cornerstone doctrine. In short, the arrogance of the fact-thumping New Atheist is equivalent to the arrogance of the Bible thumping religionist who claims that the Resurrection of Christ and the Harrowing of Hell are not stories, but facts; and what’s more, any refusal to accept the doctrines will earn you excommunication in this life and eternal damnation in Hell in the life to come. As we saw last month in “Scientism Poisons Everything,” such fanatical attitudes are not foreign to New Atheists.

Followers of TheScience™ will object that these are not comparable, as though the analogical mind has no business here because one mustn’t compare material realities with fiction. We mustn’t conflate the inner and outer worlds. I couldn’t agree more. The question then hinges on being very careful in our discernment about what constitutes inner and what outer. Too often both science and religion find this process beyond their skill set. That’s when we get ideological lockdown, cognitive necrosis and cultural recidivism. The Law of Gravity was not discovered or written by Nature; it is a notational tool invented by scientists to aid in their experiments. In other words, this Law stands at the interface between outer reality and our thoughts about it. The measures we use are invented. To Nature there is no time in seconds, and there are no metres. These are arbitrary conventions we impose. This is a fundamental confusion of which Newton was aware, and which he warned us about in his famous Principia.8 We are good at attempting to align our metrics with objective analogues, but they are always analogues, and may represent impositions that get in the way of new discoveries.

Where does the irrational fanaticism come from in the case of New Atheism?—one wonders. After all, the story of science (a false history) is full of super-rational heroes who paid dearly for their heresies, but spoke out anyway. The whole mythos of science is redundant with the secular ethos. Let’s get back to Hughes’s essay for further insights on this trouble.

Stories Train the Imagination

Hughes proposes three possible states of any individual imagination: (a) no imagination, (b) an inaccurate imagination, or (c) an imagination both accurate and strong. These states of imaginary power, he explains, correspond with certain broad personality types. A person with no imagination, “who simply cannot think what will happen if he does such and such a thing” must “work on principles, or orders, or by precedent, and he will always be marked by extreme rigidity, because he is after all moving in the dark”:

We all know such people, and we all recognize that they are dangerous, since if they have strong temperaments in other respects they end up by destroying their environment and everybody near them. The terrible thing is that they are the planners, and ruthless slaves to the plan — which substitutes for the faculty they do not possess. And they have the will of desperation: where others see alternative courses, they see only a gulf.9

In an address entitled “Is Life Worth Living?” first delivered in 1895, philosopher and psychologist William James had this to say on those lacking “scientific imagination”:

I have heard more than one teacher say that all the fundamental conceptions of truth have been found by science, and that the future has only the details of the picture to fill in. But the slightest reflection on the real conditions will suffice to show how barbaric such notions are. They show such a lack of scientific imagination, that it is hard to see how one who is actively advancing any part of science can make a mistake so crude.10

Systematised religion and science both demand a sacrifice of the imagination on the premise that they are in possession of the final revelation: “that the future has only the details of the picture to fill in,” and that therefore the imagination is a vestigial appendix better left to the surgeon.

The only way we arrive at an administrative science like the one that perpetrated the covid panic of 2020 is if the vast majority of system operators along with a vast majority of the public surrender their imaginations and therefore feel the desperate need to follow the plan set by TheScience™ because it is felt that TheScience™ is in possession of “all the fundamental conceptions of truth.” I say “surrender” despite the reality that many lacked any imagination because I witnessed a complete abnegation of this faculty among many who had well-developed minds. Such is the horror of administrative capture that it demands the complete relinquishment of one’s analogical mind, which is at once our birthright and chief bullshit detector. Systematised religion and science both demand a sacrifice of the imagination on the premise that they are in possession of the final revelation: “that the future has only the details of the picture to fill in,” and that therefore the imagination is a vestigial appendix better left to the surgeon. Consequently society is expected to demonstrate unquestioning faith because our evolution has finally arrived at its ultimate conclusion. This state of existence, as James rightly pointed out, is barbaric.

Now we have a pretty good grasp on how we arrived at this historical juncture. But what can we do about it? Hughes suggests we go about deliberately teaching the imagination, that we train and strengthen it. Following my cursory critique of the fact thumper, I suggested that we mustn’t confuse our inner and outer worlds, and indicated that distinguishing between the two can easily slip away from us, especially when we reify our supposedly objective measures. Here’s Hughes on the subject:

Sharpness, clarity and scope of the mental eye are all-important in our dealings with the outer world, and that is plenty. And if we were machines it would be enough. But the outer world is only one of the worlds we live in. For better or worse we have another, and that is the inner world of our bodies and everything pertaining. It is closer than the outer world, more decisive, and utterly different. So here are two worlds, which we have to live in simultaneously. And because they are intricately interdependent at every moment, we can’t ignore one and concentrate on the other without accidents. Probably fatal accidents.

. . .

We can guess, with a fair sense of confidence, that all these intervolved processes, which seem like the electrical fields of our body’s electrical installations — our glands, organs, chemical transmutations and so on — are striving to tell about themselves. They are all trying to make their needs known, much as thirst imparts its sharp request for water. They are talking incessantly, in a dumb radiating way, about themselves, about their relationships with each other, about the situation of the moment in the main overall drama of the living and growing and dying body in which they are assembled, and also about the outer world, because all these dramatis personae are really striving to live, in some way or other, in the outer world. That is the world for which they have been created. That is the world which created them. And so they are highly concerned about the doings of the individual behind whose face they hide. Because they are him. And they want him to live in the way that will give them the greatest satisfaction.11

To neglect this insight and refuse to look inward, Hughes warns, to remain occupied only with the objective faculty proves fatal: “The exclusiveness of our objective eye, the very strength and brilliance of our objective intelligence, suddenly turns to stupidity — of the most rigid and suicidal kind.” Following this statement, Hughes concedes a deep and troubling contradiction: that (a) this over-emphasis on objectivity is a scientific ideal without which “the modern world would fall to pieces” and “infinite misery would result,” but that (b) due to this narrow vision, our civilisation “is heading straight towards infinite misery” anyhow.12

Since then, our camera has become ubiquitous, and we’re witnessing people who mediate their lives through their cell phones. Hughes’s image of “A bright, intelligent eye, full of exact images, set in a head of the most frightful stupidity,” strikes one as prophetic.

Hughes then fixes on the camera as a manifestation of the narrow, objective view and tells the story I’ve related elsewhere about the photographer who snapped pictures of a woman being ripped to pieces by her pet tiger instead of intervening. He called this “the morality of the camera.” Since then, our camera has become ubiquitous, and we’re witnessing people who mediate their lives through their cell phones. Hughes’s image of “A bright, intelligent eye, full of exact images, set in a head of the most frightful stupidity,” strikes one as prophetic. This insight about the narrow focus of the objective mind is worth discussing further, and I intend to pull on this thread following some final remarks on “Myth and Education.”

Hughes concludes his essay by pointing out that the analogical mind is the “faculty that embraces both [inner and outer] worlds simultaneously.”13 This metaphor-making, analogical faculty “uses the pattern of one set of images to organize quite a different set. It uses one image, with slight variations, as an image for related and yet different and otherwise imageless meanings”:14

What began as an idle reading of a fairy tale ends, by simple natural activity of the imagination, as a rich perception of values of feeling, emotion and spirit which would otherwise have remained unconscious and languageless. The inner struggle of worlds. . .is suddenly given the perfect formula for the terms of a truce. A simple tale, told at the right moment, transforms a person’s life with the order its pattern brings to incoherent energies.15

To put a still finer point on it:

The character of great works is exactly this: that in them the full presence of the inner world combines with and is reconciled to the full presence of the outer world. And in them we see that the laws of these two worlds are not contradictory at all; they are one all-inclusive system; they are laws that somehow we find it all but impossible to keep, laws that only the greatest artists are able to restate. They are the laws, simply, of human nature. And men have recognized all through history that the restating of these laws, in one medium or another, in great works of art, are the greatest human acts. . .

So it comes about that once we recognize their terms, these works seem to heal us. . .The inner world, separated from the outer world, is a place of demons. The outer world, separated from the inner world, is a place of meaningless objects and machines. The faculty that makes the human being out of these two worlds is called divine.16

The concern of the poet and the philosopher is the reconciliation of the whole human being. The concern of science is one area alone to the exclusion of the other. There would be no problem with this bias in science if TheScience™ hadn’t come along to turn its narrow, objective lens on the inner world. As the late nineteenth, early twentieth century philosopher Henri Bergson put it, “I recognize that positive science can and should proceed as if organization was like making a machine. . .For its object is not to show us the essence of things, but to furnish us with the best means of acting on them.”17 It is inevitable that the objective eye will perceive the inner world as clockwork because clockwork is its only analogy. TheScience™ jettisons the imagination because it has but one metaphor. When it attempts to direct human affairs it behaves like the blithely sinister HAL 9000 in the film 2001 Space Odyssey. A great deal of science fiction has been written to warn humanity of the dangers inherent to the mechanical treatment of human affairs. But the rejection of these warnings emanating from the inner world is the hallmark of TheScience™, which has no truck with what it considers paltry fictions.

“The inner world, separated from the outer world, is a place of demons. The outer world, separated from the inner world, is a place of meaningless objects and machines. The faculty that makes the human being out of these two worlds is called divine.” - Ted Hughes

Right & Left Brain: Master & Emissary

Psychiatrist and neuroimaging researcher, Iain McGilchrist has had some insights into this troubling tendency among scientists and in our culture more broadly. In his insightful book The Master and His Emissary McGilchrist argues that our culture suffers from left-brain lockdown, a situation in which—borrowing a page from Nietzsche—the emissary (left brain) has grown contemptuous of the master (right brain) and usurped his role. The left brain focuses on grasping and manipulation—the reason the vast majority are right-handed. Consequently the perspective of this hemisphere is utilitarian. It seeks to distinguish objects, identify patterns and render things familiar enough to act upon them (or react to them) automatically. By breaking things down in this manner, it establishes a mechanistic view of the world that relieves us of stress through its high-definition clarity and predictive acumen. Crucially it has command of language. Without the right brain however it does not understand context and therefore cannot process metaphor, humour, mendacity and all manner of subtlety. The left brain is a data processor and therefore atomises and pixelates the world into mere data points.

Context is the domain of the right brain. It attends to the peripheries, to the unknowns that lurk outside the narrow focal point. Significant to our discussion, the left brain is also the side that focuses the eye—the characteristic Ted Hughes intuitively grasped when fixing upon the camera lens and in coming up with that statement about “A bright, intelligent eye, full of exact images, set in a head of the most frightful stupidity.” It is the right brain that enjoys facial recognition, the reading of body language and thus empathy. It perceives the individuality and uniqueness to which the left brain is blind.18

But because it is not in possession of language, the right brain cannot communicate directly. It needs to recruit the left brain to find expression, hence the left brain’s role as emissary. This is why the left brain finds the right brain dumb, both literally and pejoratively. Without the right brain though the left winds up too immersed among the predetermined objects and predictive circumstances of its worldview to recognize new information. Significantly too it is the right brain that contextualizes the self in the real world. In other words, abandoned to its own lights, the left brain succumbs to an idealized version of things as it has determined them to be, and slips into automatism. Vitality, creativity and imagination belong to the right brain. As a result even followers of TheScience™ who hope to convey something original cannot operate purely with the left brain. What we do find in their behaviour however is a detrimental preference for left-brain function at the expense of right-brain insight.

“In the most extreme cases, a patient will not only deny that the arm (or leg) is paralysed, but assert that the arm lying in the bed next to him, his own paralysed arm, doesn’t belong to him! There’s an unbridled willingness to accept absurd ideas.” - Iain McGilchrist

Hopefully your analogical mind is being activated here and you can see the correlation of left and right brain with outer and inner worlds, even appreciating the troubling circumstance that both hemispheres form one internal organ. If you consider yourself a practical, no-nonsense type, you are likely taking sides, cheering for the left brain, for the outer world, the perception of objective, hard facts. But brain science tells us you are indulging an illusion because, as McGilchrist explains, “the left hemisphere. . .is expert. . .at finding quite plausible, but bogus explanations for the evidence that does not fit its version of events.” Indeed not only is there something frightfully stupid about the left brain, it is also a liar and dissimulator with a love of authority. Those “slaves to the plan” that Hughes criticized may also be seen as left-brain automatons:

It will be remembered from the experiments of Deglin and Kinsbourne that the left hemisphere would rather believe authority, ‘what it says on this piece of paper’, than the evidence of its own senses. And remember how it is willing to deny a paralysed limb, even when it is confronted with indisputable evidence? Ramachandran puts the problem with his customary vividness:

“In the most extreme cases, a patient will not only deny that the arm (or leg) is paralysed, but assert that the arm lying in the bed next to him, his own paralysed arm, doesn’t belong to him! There’s an unbridled willingness to accept absurd ideas.”

But when the damage is to the left hemisphere (and the sufferer is therefore depending on the right hemisphere), with paralysis on the body’s right side,

“they almost never experience denial. Why not? They are as disabled and frustrated as people with right hemisphere damage, and presumably there is as much ‘need’ for psychological defence, but in fact they are not only aware of the paralysis, but constantly talk about it . . . It is the vehemence of the denial - not a mere indifference to paralysis - that cries for an explanation.”19

Surely we are all familiar with folk who deny having said something or having behaved a certain way immediately upon having performed the action. No doubt we have all witnessed that type who will publicly go out of their way to perform the denial. I have in mind an incident with an acquaintance who counted himself a hot sauce aficionado with a mouth and gut perfectly inured to the heat of all peppers. Upon an outing when he heaped on schug—a sauce with which he was unfamiliar—and turned red, began to cough, tear up and break out in a sweat, he claimed that it was not a reaction to the heat of the sauce, but instead that it had merely caught in his throat. He blamed the consistency of the sauce, derided the flavour, claiming it was flavourless, and went as far as to ask the staff about the nature of this horrible sauce. He spoke of it for some minutes as though to convince himself of his ridiculous narrative, and was impervious to the teasing of his comrades. I later witnessed similar behaviour from the same individual in ensuing circumstances. (Is it coincidence that he worked as an administrator in the civil service?) McGilchrist tells us that “The left hemisphere is not keen on taking responsibility. If the defect might reflect on the self, it does not like to accept it.” If however “something or someone else can be made to take responsibility - if it is a ‘victim’ of someone else’s wrongdoing, in other words - it is prepared to do so.”

Ramachandran carried out an experiment in which a patient with denial of left arm paralysis received an injection of harmless salt water that she was told would ‘paralyse’ her (in reality already paralysed) left arm. Once her left hemisphere had someone else to blame for it, it was prepared to accept the existence of the paralysis.

Ramachandran again: ‘The left hemisphere is a conformist, largely indifferent to discrepancies, whereas the right hemisphere is the opposite: highly sensitive to perturbation’. Denial, a tendency to conformism, a willingness to disregard the evidence, a habit of ducking responsibility, a blindness to mere experience in the face of the overwhelming evidence of theory: these might sound ominously familiar to observers of contemporary Western life.20

The Master and His Emissary was first published in 2009, around the time Fauci and Gates’s “systems” were changing the meaning of the term “pandemic” to exclude the notion of causing vast injury and death in order to make the category trump the reality. And as I demonstrated in Scientism Subverts Secular Society, Fauci and Gates both invoked this left-brain denial of data and real world impacts of their misguidance and malpractice. In fact on paper the whole Western world engaged in the same form of denialism, whilst attacking those who invoked the actual data and realities, calling them “deniers.” It was enough to make one’s head turn a full 360 degrees on itself. What the heck was going on? Madness? Mass formation psychosis, as some believed?

According to McGilchrist, “A sort of stuffing of the ears with sealing wax appears to be part of the normal left-hemisphere mode. . .Evidence of failure does not mean that we are going in the wrong direction, only that we have not gone far enough in the direction we are already headed.”21 If you recall, this refusal to acknowledge failure and double down was Bill Gates’s way of dealing with the so-called vaccines and lockdowns that neither killed the virus nor stopped its spread, but instead injured and killed an unconscionable number of people, devastated lives, gutted livelihoods and destroyed economies.

As for Fauci’s apparent inability to reason clearly on the subject of science and how one ought to obey its diktats without question while at the same time accepting its unreliability as a system undergoing continual reassessment, McGilchrist tells us, “To the left hemisphere, a thing once known does not change. . .the left hemisphere achieves, through this process [of imposing an unreal stasis], power to manipulate, which I would claim has always been its drive.” The left brain generally dominates the manipulative function, hence the predominance of right handedness; and narrow focal vision similarly supports the handling of objects. Analogically, manipulation of the physical world manifests as power over others, status and power in the world. It is very important to the left brain that its assessments be correct and its conclusions deemed right, and that therefore its commands be followed. In contrast, it is the “right hemisphere [that] makes it possible to hold several ambiguous possibilities in suspension together without premature closure on one outcome.”22

For individuals suffering from left brain lockdown “the differences inherent in actual individual things or beings are lost, but those derived from the system [of classification] are substituted.” In other words the rules determine the realities. Such persons, Hughes’s “planners,” no longer observe reality and evolve accordingly, but instead conform to a playbook. Those are the ones Hughes accused of having no imagination. But left brain predominance also accounts for those in Hughes’s second category, who have an inaccurate imagination. This problem is tied into the left brain’s need for certainty especially in uncertain circumstances. McGilchrist describes a left brain reflex to bypass reality in the absence of data and impose certainty where there is none.23 The interesting part here is the left brain does in fact ply a form of imagination after all, one “known as confabulation, where the brain, not being able to recall something, rather than admit to a gap in its understanding, makes up something plausible, that appears consistent, to fill it.”24

“A sort of stuffing of the ears with sealing wax appears to be part of the normal left-hemisphere mode. . .Evidence of failure does not mean that we are going in the wrong direction, only that we have not gone far enough in the direction we are already headed.” - Iain McGilchrist

Ambiguity & Uncertainty

In attempting to understand Hughes’s intuitions through McGilchrist’s clinical observations, we come to understand that the problem of imagination, which at first appears to be a simple left brain / right brain divide, in which the left brain is strictly without imagination, while the right brain alone is imbued with the imaginative faculty, in fact has more to do with kinds of imagination. The left brain is prone to abstraction, idealism through categorization and disconnection from the real world as it favours its charts and theories over what is actually presented in front of it. In a way the left brain is a fantasist that couches its terms in objective jargon and measures. Meanwhile the right brain perceives accurately the uncertainty, the ambiguity, the chaos and flow; it sees the big picture, anticipates the peripheral and not yet manifest and therefore withholds judgement and cautions humility. Therefore any education of the imagination, if it is to succeed, must train the left brain to work for the right, and not the other way round.

Most significant to my argument is that the analogical mind is exclusive to the right brain. “Only the right hemisphere,” McGilchrist informs us, “has the capacity to understand metaphor.” And in case there were any doubt as to why this matters, he further tells us that “Metaphoric thinking. . .is the only way in which understanding can reach outside the system of signs to life itself. It is what links language to life.”25 McGilchrist remarks how the term metaphor comes from the Greek meta-, meaning across and pherein, meaning to carry, implying that metaphor “carries you across an implied gap.” “Let me emphasise,” he notes, “that the gap across which the metaphor carries us is one that language itself creates.” In other words, “Metaphor is language’s cure for the ills entailed on us by language.”26 The central concept here is that words are analogically put for experiences. And this analogical process of putting for creates a gap that the words hope to bridge. Some process or faculty of mind, however, must alert us of this gap. This reflexive awareness is distilled consciousness; it is the mind looking at itself with an awareness that it is doing so. Where the left brain hides its processes behind screens of objective guides and measures, the analogical mind reveals both its own processes and those of its arrogant counter-hemisphere.

That we can render so much from limited data sets like poems and stories suggests that the much greater and grander data field of natural phenomena must represent a truly infinite potential for exploration and understanding. Therefore, our scientific conclusions ought to be understood in this context, not as final, but as useful within a limited frame.

As I close this essay, I’d like to return to Hughes’s ideas regarding the central role of story telling in the formation of our consciousness. Though ultimately balanced we’ve drifted perhaps too far into left-hemisphere territory in terms of the certainties of our explanations, and I’d like to point us back to that mysterious side Hughes invoked when he spoke of

all these intervolved processes. . .our glands, organs, chemical transmutations and so on. . .striving to tell about themselves. . .about their relationships with each other, about the situation of the moment in the main overall drama of the living and growing and dying body in which they are assembled, and also about the outer world, because all these dramatis personae are really striving to live, in some way or other, in the outer world.

Our bodies are an assemblage of entities, energies, synergies and discords. We are an ecosystem supporting bacteria, archaea and fungi that in turn support our own organism. And Western medicine recognizes only the human machine and its chemistry. Beyond our bodies are our families and communities that operate as larger organisms before which our objective eye is useless. One need only look at the unpredictability of our economics and the behaviour around markets to conclude how tenuous is our grasp of group dynamics. So we need stories, for our stories “are little factories of understanding” out of which “[n]ew revelations of meaning” emerge, “open[ing] out of their images and patterns continually, stirred into reach by our own growth and changing circumstances.”

We must remain open. And the best way to remain open is to take in as many stories as we can so that they may enter into dialogue with each other and yield ever new insights from what appears to be their limited data sets. That we can render so much from limited data sets like poems and stories suggests that the much greater and grander data field of natural phenomena must represent a truly infinite potential for exploration and understanding. Therefore, our scientific conclusions ought to be understood in this context, not as final, but as useful within a limited frame. The alternative is to shed the various stories necessary to a healthy, active and creative inner world, or consciousness, and to replace that analogical dynamic with a mechanism, an algorithm set by systems, institutions and the textbook approach to learning. The result: a society of obedient robots who have no reference points with which to compare and contrast the singular (often false) narrative with which they’ve been programmed.

No doubt, some will object that science does not tell stories and has no truck with fictions, especially false ones. Such a position however is uninformed. I’ve addressed this misguided assumption by examining some of the most glaring examples of story telling and mythologising that science indulges in “Science is Just a Bunch of Stories.” Analogy magazine keeps working to dismantle the false sense that science is somehow an exceptional and transcendent realm of human activity that yields the one True Truth. The pursuit of Truth is an ancient human quest and not only the concern of science in its present institutionalised form. In a future article, I’d like to show how science emerged from religion and still has fundamental roots in religion—not just Christianity but also ancient spiritual cults like the Pythagoreans. The present day emergence of a reductive and quasi-religious, orthodox scientism, then, should be no surprise.

Asa Boxer’s poetry has garnered several prizes and is included in various anthologies around the world. His books are The Mechanical Bird (Signal, 2007), Skullduggery (Signal, 2011), Friar Biard’s Primer to the New World (Frog Hollow Press, 2013), Etymologies(Anstruther Press, 2016), Field Notes from the Undead (Interludes Press, 2018), and The Narrow Cabinet: A Zombie Chronicle (Guernica, 2022). Boxer is also a founder of and editor at analogy magazine.

Hughes, Ted. Winter Pollen: Occasional Prose. Ed. William Scammell. London: Faber and Faber, 1995. pp. 137-8.

It is arguable whether Plato actually made this argument, but that needn’t concern us here.

Ibid. pp. 138-9.

Ibid. pp. 139-40.

Ibid. pp. 140.

Ibid. pp. 141-2.

Donaldson, Jeffery. Missing Link: The Evolution of Metaphor and the Metaphor of Evolution. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2015. p. 184.

It is critical to note that Newton was very careful to warn theorists away from mistaking what we call “time, space, place, and motion” with their true existence because physics concerns itself exclusively with “measured quantities.” Specifically he says:

Wherefore relative quantities are not the quantities themselves, whose names they bear, but those sensible measures of them (either accurate or inaccurate), which are commonly used instead of the measured quantities themselves. And if the meaning of words is to be determined by their use, then by the names time, space, place, and motion, their [sensible] measures are properly to be understood; and the expression will be unusual, and purely mathematical, if the measured quantities themselves are meant. On this account, those violate the accuracy of language, which ought to be kept precise, who interpret these words [time, space, place, and motion] for the measured quantities. Nor do those less defile the purity of mathematical and philosophical truths, who confound real quantities with their relations [analogies] and sensible measures.

In other words, we do not know true realities or even true measures because all we have at hand are heuristics, and we must therefore be careful not to confuse any clock with real time, or any measure with real space, or shape with real place.

Newton, Isaac. Principia. Trans. Andrew Motte (1729) and Florian Cajori (1934). London: University of California Press, 1934. p. 11.

Hughes op. cit. p. 142.

James, William. The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy. New York: Dover Publications, 1956. p. 53.

Hughes op. cit. p. 143-5.

Ibid. p. 146.

Ibid. p. 150.

Ibid. p. 152.

Ibid. p. 153.

Ibid. pp. 150-1.

Bergson, Henri. Creative Evolution. Trans. Arthur Mitchell. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, (1998) 2017. p. 93.

McGilchrist, Iain. The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010. p. 71.

Worth noting here that McGilchrist clarifies in his introduction that he is discussing “left” and “right” hemispheres in terms of common, general function. He acknowledges the oversimplification and over-generalisation here: that left and right can, for instance, be reversed in many individuals and that up/down and front/back are also in play when it comes to analysing brain function. His focus on the hemispheric duality is therefore purposeful. “It is this [right/left divide], I believe, that underlies a conflict that is playing itself out around us, and has, in my view, recently taken a turn which should cause us concern.” (see pp. 10-13).

Ibid. p. 234.

Ibid. p. 235.

Loc. cit.

Ibid. p. 82.

Ibid. p. 81.

Loc. cit.

Ibid. p. 115.

Ibid. p. 116.

How to broaden the inner world of a child growing up in a society that teaches him to neglect his own imagination? It seems that our materialism orients us toward disdaining the deep, sustained, meditative contemplation necessary for exploring the truths and insights in the oral/written stories handed down to us from the past. I feel this dilemma with my young daughter. I read fairy tales and myths to her every night, but find it much more difficult to get her to focus on and engage imaginatively with those oral/written stories than with the image-based ones fed to her by the tv. One of the hardest struggles I have as a parent is finding ways to inspire her to develop the capacity for contemplation that the imagination requires in order for it to transform these ancient tales into living teachers of truth and insight.

I find myself hovering over this quote: “Nature abhors such oppression and will always find a way to surmount and overturn paradigms that claim a final revelation.” I have my doubts, but I really hope you’re right. Thanks for writing. I’m enjoying your work.