THE LAWS OF NATURE

My mother tells this story about attending an outdoor event when it began to rain. Someone standing close by, turned to her with a confused air and said, “But I don’t understand. It wasn’t supposed to rain.” It was an absurd statement, but one that reflects a common problem with our notions of fact and reality. Weather forecasts are notoriously unreliable, and yet many religiously attend to them in order to decide how to dress for the day or to plan for the weekend, for the vacation week ahead, or for a planned event. After all, when it comes to more dramatic predictions like storms or very high or low temperatures, weather forecasts have a certain reliability to them. That said however, those who are less risk averse, will not cancel an outdoor event or a camping trip owing to a weather forecast, because they have experienced disappointment too often in doing so. Weather forecasts are as close as we get these days to the ancient practice of visiting the oracle or augur, and yet, we consider meteorology to be a science.

“It wasn’t supposed to rain” is a fundamentally misguided statement because it gives primacy to the model over the phenomenon. Surely, phenomena come first and we use models to furnish ourselves with some measure of understanding and purchase on said phenomena. The correct perspective when it rains despite the forecast, then, is that the model failed to account for the reality. Why do models frequently fail in that regard? Well, because they are heuristic devices, and not themselves realities. Just as important a question is—Why do we confuse our models for realities and reverse the relationship between heuristic devices and reality? It is equally important that we ask—To what extent do we indulge this slippage? What is the frequency of our confusion and in relation to how many phenomena?

Consider what we call the “laws” of physics. The word law as we understand it in the legal sense is itself a metaphor borrowed from the idea of a layer or stratum. Think of layers of earth or of cake in which we can observe an inherent order of processes and even a hierarchy, perhaps even priority. So laws are analogous to this built-in layering. The origins of the Latin word lex is more salient here because this was the word the late-sixteenth, early-seventeenth century philosopher Francis Bacon used in a novel way when he applied it to natural phenomena instead of to jurisprudence1 The etymology is unclear, but lex is generally taken to be connected with the Sanskrit roots lag- and lig- —to fasten. We find this root embedded in the words “obligation” and “religion” as they both imply a fastening or binding of sorts.2 So when we say that things are bound to be a certain way, we are invoking a similar concept. Of course, no one consciously thinks all these things when they speak of the laws of physics. But the attitude that nature is bound to laws as by a contract of sorts, and that these laws are as fundamental as the layered geological strata, lurk there in the etymology, and arguably by transmission and usage, these ideas underwrite our notions of scientific laws. Adding a further layer to our understanding of the so-called “laws of nature,” Owen Barfield points out in his History in English Words that when the term law was first applied in this manner, it was conceived of “as present commands of God.” He further notes, “It is noticeable that we still speak of Nature ‘obeying’ these laws, though we really think of them now rather as abstract principles—logical deductions of our own which we have arrived at by observation and experiment.”3 In other words, the lineage of the concept remains with us, and we have a tendency to think of the laws of nature as inherent to the divine design—something like the ten commandments handed down by God to humanity, but in this case handed down by God to natural phenomena.

This perspective is further reinforced by the notion that these laws have been discovered rather than imposed. By this unexamined manner of thinking, we lose sight of the fact that these laws are not law in any of its implicit, etymological senses, but are, instead, heuristics, invented principles mediated by our instrumentation (our tools of observation) and models built up from inductive and deductive methods. Considering that the laws in question come after the fact, it is erroneous to think of them as preceding the phenomena. The phenomena come first, and then we derive various principles from them. Nature, in other words, is not in any way bound to our instrumentation and principles. Our principles, however, are very much bound to our instrumentation. This circumstance entangles science in a fundamental epistemological problem: to what degree are we looking at a phenomenon directly? And to what degree are we observing it in relation to our heuristics (or through coloured glasses, so to speak)? Hence, “it wasn’t supposed to rain,” indicates this commonly inverted relationship by which we mediate phenomena through the lens of our models.

INSTRUMENTATION

Thus far, I’ve been speaking in abstractions, so let’s examine a concrete example. Our relationship to thermometers is ubiquitous. I find myself asking a friend who has just popped in to collect me before going out, “What’s it like out there?” He says, “Warm but not hot.” I look at the way he’s dressed and consider further that what he calls “warm” and “hot” might be different from my relationship to those terms. He might wear jeans when I would wear shorts. So I ask further, “What’s the temperature?” He has no idea because he is not a thermometer, and there’s nothing in nature one might observe to communicate temperature. Why? Because a thermometer is a heuristic device we use to establish a conventional standard. A thermometer is furthermore a clever method of analogy whereby we establish a relation between the volume of mercury in a glass cylinder according to essentially arbitrary, but necessarily conventional, gradations marked on the glass. Then we consider our conventional standard for room temperature and think, Okay, how much warmer or cooler is it than that? We go outside and we discover that despite all this work, it’s either hotter or cooler than we had deduced by the thermometer. Why? Because there are other factors like humidity and breeze. In short, the instrumentation only provides a piece of the puzzle. Now I must add a hygrometer and an anemometer before I have a sense of the weather. These are specialised instruments, and if I happen to use them, I will still be missing information. I’d be better off stepping outside, observing the tree tops and the clouds. In other words, I’d be better off casting aside all the mediating interventions and just letting exterior nature and the nature interior to my person provide the information I require. Despite the apparent accuracy of our instruments, they fail to account adequately for the phenomena, at least insofar as my body and the weather are concerned. If the instrumentation fails there, it is worth considering in what other ways our instrumentation falls short of accounting for other phenomena and why.

A useful concept here is one that emerged from the Alexandrian period (circa 300 BC to 650 CE) with respect to Ptolemaic cosmology. It’s known as “saving the appearances,” and was used to describe the purpose of cosmological models with respect to predicting celestial movements like eclipses and planetary conjunctions as well as to cast astrological charts and to establish accurate calendars. The original term was σῴζειν τὰ φαινόμενα (sozein ta phainomena), and, according to Owen Barfield’s book on the subject, Saving the Appearances, it was introduced in an Alexandrian Commentary on Aristotle’s De Caelo by a sixth century scholar named Simplicius.4 It is worth noting that the word σῴζειν that we translate as save did not denote in this context “that desperate expedients were being resorted to. . .(in the sense of rescuing)”5 as the idea is now used when scientists speak of “saving a theory.” Perhaps a better translation would be accounting for the phenomena. In any event, the concept included a tacit acknowledgment that the work of the cosmologist was to develop models that could best match up with the observations and do well enough to predict with, increasing accuracy, planetary behaviours. In other words, the work of cosmological science was not to discover the realities. There were various reasons why the bar was set so low—as we are likely to see it today, since we expect science to deal in final assertions of Truth. One reason for their lower expectations in this regard was the platonic notion that the world of the senses—the world of becoming—was not knowable in any final sense, but could only ever be the subject of opinion.6 It is for this reason that translators opt for “appearances” when interpreting the word φαινόμενα; they wish to communicate what we miss when we ply the term phenomena today—the platonic idea that the appearances did not match the realities. In addition, the instrumentation they were using was clumsy and most certainly could not have been mistaken for how the cosmos actually functioned.

Instead of expecting science to account for the phenomena today, we expect it to align with a teleological reality—i.e. a manifest articulation out there, awaiting a matching articulation devised by science. Some consideration of this expectation reveals what a fool’s errand such a pursuit must be, because what we’re in fact asking is that science reveal a perfect analogy to reality based somehow on its own devices. This confusion has come about through various means, not the least of which has been the increasing sophistication of our instrumentation. As with the thermometer, we wind up imposing the model on the phenomena and work furiously to confirm their alignment. And just like with the thermometer, we wind up viewing our models as primary and the phenomena as obedient to them. In other words, unbeknownst to scientists and secular science culture, our view is still essentially platonist and Pythagorean—believing in a mathematical world of forms informing and giving rise to the manifest world. This perspective represents a serious problem to those who claim to be naturalists; that is, for those who would like to think that they do not subscribe to anything mystical or supernatural.

THE MATH HEURISTIC

The issue here comes down to our attitudes toward mathematics. Much the same way the notion of a scientific law is informed by its etymology, our understanding of numbers and math is informed by ancient Pythagorean mysticism. In an unexamined way, it is assumed among many scientists and popular science fans that numbers were discovered rather than invented, that indeed, they essentially represent the language of the universe. This proposition however is erroneous; number systems have evolved much like any other language. Until the universal use of the arabic numerals (lauded for its discovery of zero), cultures worked with what they had: the Egyptians used hieroglyphs, the Greeks used their alphabet, and most of us are familiar with Roman numerals. All of these methods were cumbersome and not especially conducive to mathematics. Nevertheless some pretty sophisticated mathematical insights were still possible, and feats of engineering were not uncommon. In other words the utility of our numerals is no indication of their divine perfection or absolute alignment with natural phenomena. The arabic numerals allowed us a clarity never before possible, the way a more efficient computer language for coding allows for greater control and condensation. With arabic numerals we could better represent fractions, and ultimately our decimal system gave us an even greater sense of accuracy. Nevertheless there are dead giveaways that our mathematics is still incomplete. This insight requires a quick run-through of Pythagorean mathematics, its beliefs and its trouble with incommensurable numbers.

Pythagoras developed a system of numeric representation that bore fruits of its own. Pythagorean ideas are ill represented in arabic numerals (a much later development). In fact it takes an entirely different mindset to grasp their conception of numbers and therefore of mathematics. Arthur Koestler addresses Pythagorean tenets in his history of cosmology, The Sleepwalkers (1959), informing his readers about how this philosophical school perceived “‘philosophy [as] the highest music,’, and how they taught that the highest form of philosophy is concerned with numbers: for ultimately ‘all things are numbers’.”7 This formulation is a little gnomic, so Koestler unpacks it:

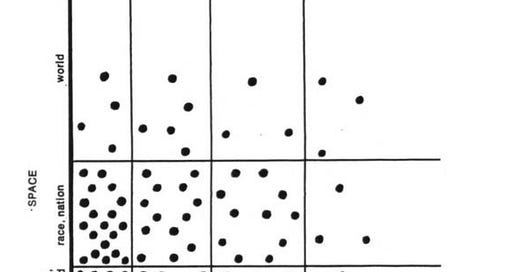

The meaning of this oft-quoted saying may perhaps be paraphrased thus: ‘all things have form, all things are form; and all forms can be defined by numbers’. Thus the form of the square corresponds to a ‘square number’, i.e. 16 = 4 + 4, whereas 12 is an oblong number, and 6 a triangular number:

Numbers were regarded by the Pythagoreans as patterns of dots which form characteristic figures, as on the sides of a dice; and though we use arabic symbols, which have no resemblance to these dot-patterns, we still call numbers ‘figures’, i.e. shapes.8

“Between these number-shapes unexpected and marvellous relations were found to exist,” Koestler continues, demonstrating some of the insights that emerged from viewing numbers in this fashion. This dot-mode of representation—which one mights see as most representative of the bean-counting origins of mathematics—crumbles when faced with the square root of 2, which cannot be represented by a dot-diagram. “And such numbers were common,” Koestler points out, “they are for instance represented by the diagonal of any square.”9 These numbers are known as “incommensurable” or “irrational.” If the tenet, all things are numbers is true, then either (a) irrational numbers describe an “ineffable” mystery—as the Pythagoreans maintained; or (b) such numbers are not numbers at all, pointing to the need for an alternative notation that might yield another rational realm, another theory altogether.

The problem that irrational numbers present has yet to be addressed as a serious problem and persists to this day. Numbers like π, φ and ψ are fundamental expressions of geometric realities and the properties of physical phenomena, and yet our system of numbers can only ever approximate them. They exist geometrically; they can be found on the number line; yet our number system—anchored in dot-diagram, atomistic thinking cannot grasp them. One would expect of a language whose claim to fame is its correlation to material processes that it would be able to clearly handle the terms most relevant to its sphere of application. But numbers were not initially conceived of in that way: instead they were bean-counting tools that were later imperfectly adapted to logic. After all, math is a shorthand that helps us condense and track our logical processes. Where quantities are useful, numbers come into play. And quantities are useful when working with heuristic measures like clocks, scales and rulers. The repurposing of a counting system to logical processes is an artificial act, not a discovery. The sense of discovery lies with the play of the analogical mind as it works up a poetic conceit tied to the driving metaphor. And the driving metaphor of our sensibilities toward mathematics, lost to time, is the mystic Pythagorean belief “that mathematical relations held the secret of the universe.”10

To put a finer point on the matter, Arthur Koestler explains, quoting Plutarch of the Pythagoreans: “‘The function of geometry. . .is to draw us away from the world of the senses and of corruption, to the world of the intellect and the eternal.’” In other words mathematics is a method of contemplating the eternal; it is “the way to the mystic union between the thoughts of the creature and the spirit of its creator.” Ultimately, Koestler observes, “The Pythagorean concept of harnessing science to the contemplation of the eternal, entered, via Plato and Aristotle, into the spirit of Christianity and became a decisive factor in the making of the Western world.”11 To this day, we maintain a mystical veneration of mathematics, calling sciences based on math “exact” and “pure.” Consider for a moment how your veneration of math boils down to two assumptions: (a) that it clears away the clutter of the phenomena, and (b) that it somehow transcends the errors of human thinking. Now consider what we’ve just reviewed: that mathematics is a language, indeed a product of thinking.

THE PROBABILITY HEURISTIC

Once again, I’ve been speaking conceptually, so let’s ground these observations in something concrete and as commonplace as the weather and thermometers. It bears repeating that the issue here—as stated in the second paragraph of this paper—is how we confuse our models for realities and reverse the relationship between heuristic devices and reality and how pervasive this problem might be. Let’s take a look at a popular favourite: probability.

Let’s start with the ubiquitous coin flip. Many experiments have been done and some complex math can be applied, but we’re going to keep things simple. Furthermore, the internet will tell you that real world coin flipping, even mechanically driven, does not conform to the theoretical model. Although such information helps reinforce my thesis, I’m going to proceed with the theoretical rudiments to make what I hope is a deeper point. So let’s presume the chances for a heads or tails outcome are indeed 50-50, which is shorthand for 50%:50%. That’s true of one coin flip. How about two flips, three flips, four? Most seem to think that the chances remain 50-50 no matter how often one flips the coin. But this is not the case. And since the misconception is so pervasive, let’s quickly review the basic principles. If the flip is truly random and I get four heads in a row, the next flip is far more likely to present tails.

Let’s put some skin in the game. Say I roll double sixes12 on a pair of dice three times in a row, what are the odds that I’ll do it again? It’s no longer 1:35 against or 2.8%. There’s a progression: the probability of rolling double sixes three times in a row is 1/46,656, which we may derive (most simply) by multiplying the probability of one roll of double six exponentially, i.e. 1/36 x 1/36 x 1/36. The odds of rolling four times in a row, we may represent as 1/36^4 or 1/1,679,616. In other words the chances recede exponentially.

Same goes for the coin toss when trying to predict the outcome of the next flip following four heads in a row. What starts out as 50-50 grows exponentially lopsided. When we go about the calculation, we take 50/100 and reduce to 1/2. Over four flips, our chances of getting four heads in a row are 1/2^4 = 1/16, and the fifth will be 1/2^5 = 1/32: if we’re thinking in terms of odds, that’s 31 to 1 against. The only way by which the probability resets at 50-50 is if human agency intervenes, like when a friend holds out two hands and asks you to guess over and again which one is hiding the ball. Once we remove what we call “randomness” from the equation, the terms reset at each iteration.

All of this probability stuff is indeed fascinating, but the main issue that we lose sight of is what probability can’t tell us: the actual outcome of any given event. In other words, probability is an extremely clever workaround to compensate for what we do not know and cannot predict about the phenomena. So what the terms 50-50, 1/2^5 and 1/36^4 obfuscate is that truly random events are not, in fact, predictable; if they were, coins would land on heads then tails then heads again in succession. In other words, probability is not how the universe works. Instead it is most evidently a heuristic device we use to get around the fact that we don’t know and cannot predict the behaviour of the phenomena. In other words, it would be foolish to assume that probability represents the phenomena in any direct way. Much like those ancient cosmologists, what probability does do is account for the phenomena in an applicable and useful manner. To put it another way, the phenomena do not obey the laws of probability. Such a take is an inversion of the relationship between our models and realities, and is of the same order as believing that the weather ought to obey the weather forecast. When we perceive the world in this manner, we are subscribing to a scientistic metafiction instead of to a true metaphysic; we are indulging in a modern form of superstition.

Although probability is an ingenious, indirect approach, it reveals quite a lot about the phenomena—the way we might imagine echolocation reveals quite a lot without quite providing a true picture. What probability reveals however is not what we generally attribute to it. For instance, it tells us less about outcomes and more about the implications of distribution and increasing-decreasing likelihoods. How does the universe know that following several successive outcomes of heads, the next flip of the coin should be tails? Why doesn’t it reset back to 50-50 with each toss? Surely this phenomenon implies (a) some sort of cosmic memory, (b) a continuity of action, and (c) an open-ended future. What we generally call “randomness” and “probability” obfuscates these conclusions, in part because we entertain a certain predetermination or predictability in the so-called “laws of probability.”

I have another anecdote like “it wasn’t supposed to rain” to supply a more pedestrian side to the problem of reversing the relationship between model and phenomenon. In this case, I was at a bar when an acquaintance showed me a nickel, and by humorous slight of hand, which was essentially a fumbling about his person, slipped the nickel in his shoe, then presented me with two closed fists and asked me to guess in which hand the nickel was. I laughed and told him that much like in a shell game, it was in neither hand, and that, besides, I’d seen him put it in his shoe. Nevertheless, like a pro at the shell game, he insisted that I guess which hand, and added that he would give me $200 if I guessed correctly, but that I’d have to pay as much if I guessed wrong. The banter proceeded with equal incoherence until we were joined by a young man who proudly stated that he was a statistician. He asked, “How many guesses can I make?” The shell game master guffawed and didn’t commit, but made the statistician feel very clever. This was all in good fun and no money was exchanged. However, the moral of the story is that the statistician had missed the shell game aspect entirely because he was focused on the stats. In other words, he wasn’t observing the phenomenon at all. Instead, he was imposing his model where it had no relevance. The whole point of a shell game is to turn the odds paradigm against the gambler. I’ve called this a pedestrian example; but I mean to suggest by this commonplace tale how pervasive and reflexive is our habit to impose scientific models, and furthermore, how we wind up duped in the process.

THE TAUTOLOGY OF SCIENTISTIC METAFICTIONS

In The Selfish Gene (1976), Richard Dawkins says, “What I have now done is to define the gene in such a way that I cannot really help being right!”13 A few pages later, he admits that his method proceeds “tautologously.”14 This self-consciousness would be commendable if the author took it for a serious flaw. Often enough, after all, a tautology amounts to a form of circular reasoning—a classic logical fallacy. The famous philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein argued in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922) that tautologies are essentially meaningless:

4.461 The proposition shows what it says, the tautology and the contradiction that they say nothing.

The tautology has no truth-conditions, for it is unconditionally true...

. . .

4.462 . . .

In the tautology the conditions of agreement with the world—the presenting relations—cancel one another, so that it stands in no presenting relation to reality.15

So what does this mean practically speaking? When asked to make a statement of scientific fact, common answers range from “gravity” to “the sun rises in the east.” Folks are not generally sophisticated off the cuff. If pressed, they will self-correct: “well, okay, the sun doesn’t exactly ‘rise’—the rotation of the Earth on its own axis gives the appearance of a rising sun.” That’s a scientific fact. Gravity, however, is a problem. In what sense is gravity a fact? Let’s set that aside for a moment. Instead, let’s return to our thermometer. One might say, “It’s a scientific fact that water freezes at zero degrees celsius and boils at one-hundred.” Now there’s an obvious tautology. It’s a statement that amounts to nothing because the celsius scale was designed to give such readings. In other words, the markings on the vile of mercury were determined by the freezing and boiling points of water. The statement is circular and therefore says nothing. More often than not, this is the sort of thing we take for scientific facts.

When it comes to gravity, if we’re talking about the acceleration of a falling object, the numbers we work with are determined by the scale employed, whether metres or feet, and then by seconds, that is, by clock time, which is a measure of oscillations, a relational contrivance of our own, found nowhere in the natural world. In other words, the terms of the so-called fact are defined by the instrumentation. The phenomena are thus thrust aside in favour of the metrics. We impose our models.

When we say “the sun rises in the east,” we encounter the same trouble because the term east is defined by the place where the sun rises. Etymologically speaking, philologists hypothesise that east comes from the proto-Indo-European root, aus-, meaning, “to shine, especially of the dawn.” More recently, the term comes from Proto-Germanic aust- “literally ‘toward the sunrise’.”16 In other words, the statement, “the sun rises in the east” amounts to saying “the sun rises where the sun rises.”

What we’re left with upon scrutinising these examples are the following facts: (a) falling objects accelerate; (b) the Earth turns on its axis; and (c) water can freeze and evaporate. Statements of so-called “accuracy” about the phenomena are impositions that are not factual, but tautological. Our instrumentation specifying time, distance, place and temperature are all heuristic guides, conventions that can be useful for purposes of communication in regard to the phenomena and for the purposes of manipulation of the phenomena. The instrumentation, as noted, is demarcated with numbers that we then use in our mathematics, all too often oblivious to the fact that the numbers employed are arbitrary and have little to do with the phenomena in any inherent sense. With that understanding set aside or obfuscated, we then make the assumption that we’re dealing with a “pure” and “exact” method providing us with epistemological truth regarding the phenomena. It should go without saying that the application of these various heuristics is useful and productive. What I’m getting at is they need not also be considered facts about reality, though they do, at times, imply certain facts.

To make matters worse there are often complications even with those statements of fact. Statement (a) above, for example requires qualification because not all falling bodies accelerate—buoyancy, displacement, and relative temperature are important variables. The other two statements seem general enough to present no problems. But when we specify a rate of acceleration, we run into trouble again: variables like friction, shape of object and medium (air, heavier vapour, water), then require consideration. And when we provide a temperature for water freezing and evaporating, the celsius scale provides us with only a guideline because it pertains specifically to pure H2O at sea level—neither of which conditions are found together in nature.

To summarise, scientific tautologies emerge from two sources, the most obvious being those arising from instrumentation and hypothetical (including theoretical) models. We find less glaring, that is, more hidden, instances in circular definitions like Dawkins’s implicitly ethical argument about selfishness being ontologically inherent to genetic processes. Because tautological truth statements are often taken to be fundamental, and are often used as foundational notions, many areas of science build their theories on metafictions instead of what we expect to be solid, epistemologically grounded metaphysics.

RUNAWAY METAFICTIONS

Some might object here and claim that I am not examining actual scientific facts, but oversimplified popular conceptions of scientific facts. True. But hold on. I am getting to some very real science in just a moment. This is not the place to enter into the details of the various sciences and disentangle the tautologies from the facts. That project would occupy several tomes and should be left to those more qualified than me. My purpose here has been to demonstrate our habits of thinking; and these habits of thinking do indeed permeate the minds of scientists, including Darwinists like Dawkins and statisticians like the young man from my anecdote. The point I’ve been driving at, if you recall, is that we confuse our models for realities and reverse the relationship between heuristic devices and reality. I have provided accessible examples that can be applied analogically here-forward by those with a mind to do so.

Our trouble with inverted reasoning is problematic in all manner of ways; but most urgently, at present, this sort of fallacious approach to the phenomena is generating some very worrisome conclusions about our world and humanity’s place in it. When it comes to our planet, we’ve come to believe that certain quantities are desirable and others are undesirable based on computer models. The ethos of UN and globalist policy initiatives is driven entirely by this inverted relationship of model to phenomena. Instead of basing models on the phenomena and trying to best account for them, governments—plying what they believe are scientific rationales—are now trying to make the phenomena (including human beings) fit the models. The results can only be disastrous. Indeed, they already have been. Perhaps it bears stating that this habit of mind is not the sole cause of our errors or of our present predicaments. Many factors are intervolved with the subject under analysis here. But these lie beyond the scope of this study. The object of this essay is to bring to light what seems to be a submerged and unexamined relationship to our scientific models in order to gain a greater intellectual purchase on them and to thwart a paradigm that would enslave us to its diktats.

Back in March 2020, a paper emerged from Imperial College-London (ICL), under the lead authorship of epidemiologist Neil Ferguson, predicting that 2.2 million people would soon die of covid in the U.S. alone if strict lockdowns were not put in place. Although the paper17 presented this forecast as a worst-case scenario generated by its computer modelling, Ferguson flogged this alarmist message to the media and to governments around the world, and the message that reached the public and policy makers was that this was the scenario for which we ought to responsibly prepare. In other words, the Ferguson modelling was a lot like the weather forecasting problem I presented at the start of this paper. The difference is that instead of invoking the sentiment It wasn't supposed to rain, the ICL pandemic forecast asserted 2.2 million will die in the U.S. alone. Moreover, both these types of forecasts entail a recommendation. When it comes to the weather, one might bring an umbrella or warm clothing. When it comes to a pandemic forecast, however, the recommendations are more consequential. Indeed, the result of the Ferguson model was a period of over two and a half years of public policy panic, including lockdowns that violated human rights, devastated economies, destroyed small businesses, decimated families, led to delayed medical procedures (with untold years of damage and lost life), delayed education and child socialisation, and also led to skyrocketing mental illness and depression rates, drug addiction, addiction relapses along with related overdoses and a spike in suicides.

When it comes to a false weather prediction, one might get wet or cold or dress too warm or wind up carrying an umbrella for no reason; but in the case of a false pandemic prediction, the consequences are far more severe. The crux of the trouble in this instance lies with a disposition of our present society to value scientific models over and above traditional socio-political models. To clarify, the models in play in a democratic society include humanitarian orientations that have been codified in charters of rights and documents like the U.S. constitution. Such models of governance have been developed over centuries of negotiation with kings and princes (Magna Carta, 1215), and were later honed in parliaments during the Enlightenment and via various revolutionary actions. The pluralistic, democratic model constitutes our social contract and was the the one in play when the pandemic was declared; and it was this model that was displaced by a novel, scientific model that suggested the democratic, pluralistic one would lead to mass death. So to return us to the main thesis again—the evolving socio-political model which has been working to emancipate and benefit more and more people for hundreds of years by encouraging freedom (which we may look at as freedom of human phenomena), was suddenly overturned in favour of a model with the opposite ethic. The earlier contract was developed through negotiations (and where those failed, various wars), and was therefore a descriptive model arising from the phenomena, whereas the new scientistic one was a model imposed on the phenomena, a tyranny. Unlike the phenomena like the weather, when the phenomenon in question is a human population, and the phenomenon is made to serve or fit a given model, the issue becomes ethical.

Based on the ICL Ferguson paper, governments around the world seized health emergency powers (which are still in effect nearly three years later), allowing them to adopt extreme measures that provided grounds to coerce citizens against their wishes to take dangerous and experimental medical interventions mislabelled “vaccines” that have caused serious, longterm injuries at unprecedented rates.18 Once again, the problem may be framed as a misapplication (a reversal) of our modelling vis a vis the phenomena. When it comes to vaccines there are several modelling issues to consider. Until this latest false alarm, a vaccine was defined as a preventative medical intervention providing a sterilising effect. In other words, vaccines were sold as products that would prevent infection and help the body kill off a virus. The logic of the model was that if one took the vaccine, one was rendered immune to the virus. What happened however was that the term vaccine was changed to include a non-sterilising medical intervention that does not render immunity. Consequently, the logic of its deployment was lost. Nevertheless, the vaccination model remained in place and its application was rolled out in an unprecedented manner. Once again, a scientific model took precedent over the phenomena.

As mentioned above, when the phenomena in question are human beings, the issue becomes ethical. This last violation of personal autonomy over one’s own body is unconscionably egregious and frightening, especially considering that it was the Nazis who introduced this sort of unethical experimentation on human beings. In the wake of such atrocities, humanity developed what came to be known as The Nuremberg Code (1947), which codified the rights of the individual with regard to the acceptance or rejection of experimental medical interventions. The first point of the ten-point document reads as follows:

The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential.

This means that the person involved should have legal capacity to give consent; should be so situated as to be able to exercise free power of choice, without the intervention of any element of force, fraud, deceit, duress, overreaching, or other ulterior form of constraint or coercion; and should have sufficient knowledge and comprehension of the elements of the subject matter involved as to enable him to make an understanding and enlightened decision…19

Despite this document—a model for ethical human behaviour where medical procedures and pharmaceuticals are concerned—governments, institutions and many businesses dragooned citizens to accept the experimental pharmaceuticals with threats they’d lose their jobs and face other penalties, including being barred from public spaces, businesses and travel, and in some cases even face financially ruinous fines and even prison sentences.20 This is how scientific models wind up imposed on human phenomena. Ignorant and frightened citizens, influenced by media hysterics and stoked by celebrity opinion, went as far as to suggest that the “unvaccinated” should be denied medical care. The rationale throughout the false covid panic was represented by the ubiquitous slogan, Follow The Science—the assumption being that modern science has better models than those established by human trial and error over several millennia. Although this Follow The Science motto strikes many as being unscientific, and indeed reminiscent of Martin Luther’s sola fides—your salvation lies in faith alone—many have taken the follow-the-science credo as an affirmation of allegiance with the scientific method and its foundation in exactness and purity.

In case some readers draw the conclusion that the covid false alarm was a one-off case of mismanagement, I’d like to briefly draw your attention to previous bungles and demonstrate how the covid debacle was a culmination of our tendency to reverse the proper relationship of model to phenomena. Unfounded global alarmism took hold on at least two previous occasions in recent history, first in the late 1990s, early 2000s with regard to the Mad Cow panic.21 As public policy expert Phillip Magness explains the problem with Ferguson’s modelling, the “line of argument falters as social science because it assumes the validity of the very same forecast it purports to demonstrate.”22 In other words, the trouble here is steeped in tautology and the fallacy of circular reasoning—a not uncommon problem in the sciences, as noted above.

Reading Magness’s articles along with the Spiegel article cited below with reference to the Swine Flu panic, some observers will note that it’s not science that’s at fault in these instances, but instead political and pharmaceutical interests. Plenty of scientists, after all, were sounding alarm bells about the shoddiness of Ferguson’s work.23 As it happens, for instance, viruses do not spread and kill exponentially, but instead follow what’s known as a gompertz curve (see the notes). If we could only wash science clean of the corruption of filthy lucre, a fresh and purified science would be more than qualified to lead the way. It bears repeating that the subject under analysis here is not the only factor at play in these goings on. In fact, this point is central to the problem of designating science as “exact,” “objective,” and “pure”—somehow transcendant. Scientistic rationale is being used and couching itself in scientific language as a tool of authority.

While I’m all for finding a way to release science from corruptive influences and for ways to improve modelling, I’m also a realist who has read Horace Freeland Judson’s work, The Great Betrayal: Fraud in Science (2004), and it is foolish to think that the task of untangling science from its funding structures, dysfunctional self-policing, ambitious personalities and corporate capture is something we can look forward to. The public should not make the mistake of imposing a false model on science—a science should be this perfect pure thing, when it is in fact something else entirely, an all too human and flawed endeavour. I can see one objecting that had we used other and better scientific models instead of those ICL-Ferguson ones, we would not have taken bad advice. The problem was with the experts consulted, not with science. But (a) how is one to determine a correct scientific model from an incorrect one? (b) who chooses the experts (aren’t all involved certified scientists?) and (c) the problem wasn’t only owing to a single flawed model: political and corporate interests were also in play deciding points (a) and (b). Furthermore, let’s not lose sight of how one’s sense of having a scientific orientation can lead to missing the shell game. Owing to the biases inherent to its own paradigms, science alone cannot hope to self-correct and provide authoritative models upon which to remodel society. Faced with a scientistic revolution, it seems we’ve arrived at an historical moment when we need to consider a division of science from state, establishing limitations on scientific models and recommendations where they come into conflict with established models of governance.

That said, I still maintain that even if we managed to develop an emancipated, truly pure science, the hope that it would produce predictive models to which we ought to conform in place of those that have arisen through negotiation is fundamentally misguided because based upon a misunderstanding of the relationship between such models and the phenomena they wish to account for. Surely our instrumentation and our models ought to serve us, and not we who ought to wind up serving them. In the cases of the epidemiological modelling I’ve just noted, the principal approach is statistical and probabilistic; and as we’ve seen, the mathematics of probability is a clever workaround not to be mistaken for reality. Meanwhile, statistics are notoriously flexible and often deployed in misleading ways. Worse, when public policy comes into play, the models make tautologous assumptions that engender runaway metafictions. Policy makers posit an ideal balance underwritten by an unconscious and unexamined ledger book analogy, setting targets for desired outcomes. While such an approach may have utility in the sphere of finance, when we look at human populations in this manner, we are imposing models on a phenomenon (human beings) in an unethical manner. Human beings are more than mere %s after all. Indeed, the % tag is inherently reductive and dehumanising. Whether the issue is equal distribution targets among various identity groups, or zero covid targets, or net zero carbon emissions, the paradigm in play is one in which we are attempting to force the phenomena to fit the model instead of the other way round. And as we’ve seen, this is a recipe for disaster.

In the spirit of stimulating some discussion, I’d like to introduce a final line of objection to the thesis I’ve proposed. If we are to quit imposing models on the human phenomenon, how are we ever to achieve any progress? All socio-political, legal and economic systems are imposed, after all. How, for instance, might a slave society manage to move away from the paradigm of slavery without the imposition of new models? At some point in time, slavery was seen to be the natural order, one arising from millennia of human behaviour. This line of questioning gets to the heart of the matter and is likely to be productive in bringing greater nuance to the claims set out here. Slavery and authority are indeed the issues underwriting the concerns of this paper, and nothing could be more paradigmatic of tyrannical models. Perhaps we need to interrogate further the sorts of models that enslave and those that emancipate. In any event, what’s clear is that science alone cannot make those decisions for us; hence the focus of this essay on scientific models and scientism. Surely we require more types of thinking at the table than this one ascendant Science, rapidly asserting its authority (through claims of purity and exactitude) as a repressive, orthodox force.

Looking forward to your comments!

Asa Boxer’s poetry has garnered several prizes and is included in various anthologies around the world. His books are The Mechanical Bird (Signal, 2007), Skullduggery (Signal, 2011), Friar Biard’s Primer to the New World (Frog Hollow Press, 2013), Etymologies (Anstruther Press, 2016), Field Notes from the Undead (Interludes Press, 2018), and The Narrow Cabinet: A Zombie Chronicle (Guernica, 2022). Boxer is also a founder of and editor at analogy magazine.

Barfield, Owen. History in English Words. Barrington, MA: Lindisfarne Books, 1967, p.148.

See Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary. www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0059:entry=lex (accessed Nov 22, 2022)

Barfield, Op. cit. p.149.

See Barfield, Owen. Saving the Appearances: A Study in Idolatry. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1988, p.48.

Ibid. p.49.

“What is that which always is, and has no becoming, and what is that which is always becoming but never in any way is? The one is apprehensible by intelligence with an account, being always the same, the other is the object of opinion together with irrational sense perception, becoming and ceasing to be, but never really being. . .perceptible things are objects of opinion and sense perception and come into being and are generated.” Plato. Timaeus and Critias. Transl. H.D.P. Lee. Ed. T.K. Johansen. Penguin Classics, 2008, pp.18-19.

Koestler, Arthur. The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man’s Changing Vision of the Universe. London: Arkana, Penguin, 1989, p.30.

Ibid. p.30.

Ibid. p.40.

Ibid. p.41.

Ibid. p.37.

Jeffery Donaldson would point out that the dots placed on the faces of a dice are themselves fictions. See his seminal article on this subject: “A Bridge is a Lie: How Metaphor Does Science.”

Dawkins, Richard. The Selfish Gene. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006, p.33.

Ibid. p.36.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Transl. C. K. Ogden. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 2016, pp.62-63.

See www.etymonline.com/word/east (accessed Nov 24, 2022)

Ferguson’s covid alarmist model from March 16, 2020: www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/sph/ide/gida-fellowships/Imperial-College-COVID19-NPI-modelling-16-03-2020.pdf (accessed Nov 24, 2022). For more on the flawed modelling, see Phillip W. Magness at AIER, March 19, 2021: www.aier.org/article/the-disease-models-were-tested-and-failed-massively/ (accessed Nov 25, 2022).

The term “vaccine” was redefined during the covid debacle such that products bearing that label no longer had to deliver immunisation or sterilisation (prevention of viral transmission)—as commonly understood by anyone who was to hear the word, “vaccine.” This was a bald-faced marketing ploy involving collusion between various health agencies and the pharmaceutical industry, conveniently categorising these shots as “biologics” rather than “drugs,” “medicines,” “therapeutics” (or “experimental gene therapeutics,” as the mRNA products ought to have been labelled).

Biologics enjoy a special status among pharmaceuticals, as they are exempt from a number of provisions affecting all other pharmaceutical substances. Most importantly to developers and producers, they enjoy legal immunity against insurance claims for injury and death caused by biologics. Additionally, these interventions on otherwise healthy persons could be fast-tracked to global markets without having to undergo the rigorous and years-long, scientific processes of safety testing. See rumble.com/v19czj9-why-did-all-vaccine-manufacturers-have-a-complete-blanket-immunity-from-lia.html (accessed Nov 24, 2022).

A well known paper in the field dating back to 2003 documents how attempts to engineer a vaccine against SARS-CoV-1 resulted in lung injury and death to lab animals due to vaccine induced suppression of natural immunity—i.e. the body’s ability to produce certain antibodies—and were inducing “vaccine enhanced disease” upon contact with live virus (and other exposures). See www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3335060/ (accessed Nov 24, 2022).

This research is especially significant because Moderna, one of the producers of the mRNA product widely distributed against SARS-CoV-2 had discovered by March 2021—at the end of their unconscionably brief testing period on humans (begun June 2020)—that their product was having a similar impact on their human subjects—a reduction in antibody production and an elevated vulnerability—meaning vaccinated groups were vulnerable to vaccine enhanced disease. See www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.04.18.22271936v1.full (accessed Nov 24, 2022).

Also see Open VAERS for injury numbers: openvaers.com/ (accessed Dec 3, 2022): “32,508 COVID vaccine reported deaths” and “184,796 total COVID vaccine reported hospitalizations” and “1,471,557 COVID vaccine adverse event reports” and “2,368,650 reports of adverse vaccine events in VAERS” total, demonstrating that over half of the events ever reported since VAERS began in 1990 have come recently from the covid vaccines.

See history.nih.gov/display/history/Nuremberg%2BCode (accessed Nov 25, 2022).

See www.newsweek.com/unvaccinated-austria-go-under-lockdown-face-1660-fine-per-violation-1649273 (accessed Nov 24, 2022).

See Der Spiegel article www.spiegel.de/international/world/reconstruction-of-a-mass-hysteria-the-swine-flu-panic-of-2009-a-682613.html (accessed Nov 25, 2022). For more on the flawed modelling, see Phillip W. Magness at AIER, March 19, 2021: www.aier.org/article/the-disease-models-were-tested-and-failed-massively/ (accessed Nov 25, 2022)

See Phillip W. Magness at AIER, April 23, 2020: www.aier.org/article/how-wrong-were-the-models-and-why/ (accessed Nov 25, 2022).

For information on the exponential growth fallacy see analogymagazine.substack.com/p/covid-19-heretic-post:

“Exponential Growth Is Terrifying.” Dr. Michael Levitt: May 14 2020. www.youtube.com/watch?v=hCgPf1SuPNY&list=PLstiHTWcxU0KAj3q-MrpxKZeJh4aHcq2i&index=1

“Curve Fitting for Understanding.” Dr. Michael Levitt: May 14 2020. www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uw2ZTaiN97k&list=PLstiHTWcxU0KAj3q-MrpxKZeJh4aHcq2i&index=2

“COVID-19 Never Grows Exponentially.” Dr. Michael Levitt: May 14 2020. www.youtube.com/watch?v=8aHrx68IT7o

In the three short vlogs featured above, Dr. Michael Levitt, professor of structural biology at Stanford University Medical School and winner of the 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, explains how data is assembled to mark the trajectory of an epidemic disease such as Covid-19, specifically how data is plotted on a curve on a graph. Contrary to the fear mongering news coming from governments and mainstream media, SARS-CoV-2 and other infectious diseases never grow exponentially in a population, be it localized or on a global scale. Instead, viruses spread through a population according to the Gompertz Function, named after Benjamin Gompertz (1779-1865). The Gompertz Curve illustrates how the growth of an epidemic is slowest at the start and end of a given time period. By using the Gompertz Curve to show the rate of growth of coronavirus cases in South Korea and New Zealand during the “first wave” of Winter 2019/20, Dr. Levitt illustrates the following findings: “From the very first confirmed case the rate of growth of Covid-19 confirmed cases is not constant. Instead the ‘constant’ exponential growth rate is decreasing rapidly. Although the growth rate is very rapid at first, it is decreasing at an exponential rate.” Dr. Levitt’s insights match well with the fact that Covid-19, like other infectious diseases, is a “self-limiting illness”: it spreads through a population, kills the vulnerable, and expires. No amount or severity of lockdown can change that. It may delay the rate of spread, but the virus will run its course through the population eventually, one way or another. Excessive human intervention in managing epidemic diseases causes no good and does much harm.

“The end of exponential growth: The decline in the spread of coronavirus.” Dr. Isaac Ben-Israel. The Times of Israel: Apr 19 2020. www.timesofisrael.com/the-end-of-exponential-growth-the-decline-in-the-spread-of-coronavirus/ This study by Professor Isaac Ben-Israel, Israeli military scientist and chairman of the Israeli Space Agency, uses data from dozens of countries around the world to demonstrate with a series of graphs how the trajectory of the coronavirus—in countries with strict lockdowns as much in those that didn’t lock down—follows the Gompertz Curve described by Dr. Michael Levitt:

“It turns out that a similar pattern—rapid increase in infections that reaches a peak in the sixth week and declines from the eighth week—is common to all countries in which the disease was discovered, regardless of their response policies: some imposed a severe and immediate lockdown that included not only “social distancing” and banning crowding, but also shutout of economy (like Israel); some “ignored” the infection and continued almost a normal life (such as Taiwan, Korea or Sweden), and some initially adopted a lenient policy but soon reversed to a complete lockdown (such as Italy or the State of New York). Nonetheless, the data shows similar time constants amongst all these countries in regard to the initial rapid growth and the decline of the disease.”

“Making Sense of Mortality with Joel Smalley – MBA, Quantitative Analyst.” Pandemic Podcast: Feb 24 2021.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=NWTaEtkZiA4&list=WL&index=16 (page removed)

odysee.com/@pandemicpodcast:c/making-sense-of-mortality-with-joel:8

In this episode of the Pandemic Podcast, British quantitative analyst Joel Smalley uses a series of graphs assembled with raw data from the UK government Coronavirus website to illustrate with painstaking detail how the pattern of transmission of the virus through the British population, during both the Winter 2019/20 and 2020/21 seasons, followed the Gompertz curve. By referring to Covid-19 as a “self-limiting event,” Smalley means that the actual trajectory of the virus itself through the two winter seasons had its own natural curve, and it would have naturally followed that pattern whether the UK had done hard lockdown or not, which is precisely what we’ve seen in comparative data analyses of countries with more and less stringent lockdown restrictions:

“The [Gompertz] model theoretically was based on the notion that [transmission of SARS-CoV-2] was decreasing exponentially in terms of growth from day one.”

Excellent essay!

If I may just make a short note.

The "Indo-European language" and the "Indo-Europeans" are pure fiction since not the slightest archaeological evidence has ever been found to support their existence nor is there any written or oral reference to any nation about our supposed "ancestors Indo-Europeans". But it is used extensively to obscure the catalytic influence of the Greek Culture and the Greek Language from the dawn of the World.

Keep up your excellent work!

So many great examples in this densely packed essay. The biggest take-away I agree with is your comment: "It bears repeating that the issue here—as stated in the second paragraph of this paper—is how we confuse our models for realities and reverse the relationship between heuristic devices and reality and how pervasive this problem might be." Phenomena is difficult to observe, particularly at the quantum level. Also, "Despite the apparent accuracy of our instruments, they fail to account adequately for the phenomena..." The later points about Covid are harder to contend with, and though 2 million Americans did not die as predicted by Neil Ferguson, over 1 million did. Lockdowns did create havoc and freedoms were impinged, but weren't lives saved by these measures? I believe they were.