Welcome to Barstool Bits, a weekly short column meant to supplement the long-form essays that appear only two or three times a month from analogy magazine proper. You can opt out of Barstool Bits by clicking on Unsubscribe at the bottom of your email and toggling off this series. If, on the other hand, you’d like to read past Bits, click here.

Last week’s Barstool Bit ended with my buddy at the pub announcing that the Bible is just a bunch of stowrees. The implication of course was that Science is better because it’s about facts. I’ve addressed the problem with facts in an in-depth piece called “What is a Scientific Fact?” It is telling that my friend at the pub did the typical thing when asked what a fact was: he picked up a beer coaster and dropped it on the bar and said, “There! That’s a fact.” He might as well have burped and uttered the same claim. The funny thing is that the idea that Science is about facts while its arch-adversary, Religion, is about stories is itself a story that Science tells about itself. As it turns out, Science tells a whole lot of stories that have nothing at all to do with fact or truth.

I’m sitting with a couple of regulars talking about alternative healing and one of them expresses scepticism on the one hand, while also confirming the positive results she experienced from homeopathy. This led to a brief trading of ideas about what science actually is, and another lady mentioned something about how science does experiments over and over and over and over and over again. Her body language was intense. She really threw her shoulders into it, rolling her arms over each other. Her point was that science was reliable because of its method, which includes confirmation of experiments through replication by third-party scientists.

Although there is some truth to this confirmation process, The Scientific Method turns out to be a completely mythical creature. There is no strict method. It just doesn’t exist beyond a vague sensibility regarding how things are properly done. Only very few experiments are ever replicated, and they tend to be things like cold fusion that have the potential to reap enormous financial rewards. There are two key issues: one is that experimentation costs a lot of money; and the other is that experiments that disprove the work of other scientists aren’t popular, don’t get published and therefore don’t get funding. There’s just no incentive there. Then we get certain repeated experiments like the ones we do in high school in the chemistry lab. Okay. Straightforward stuff.

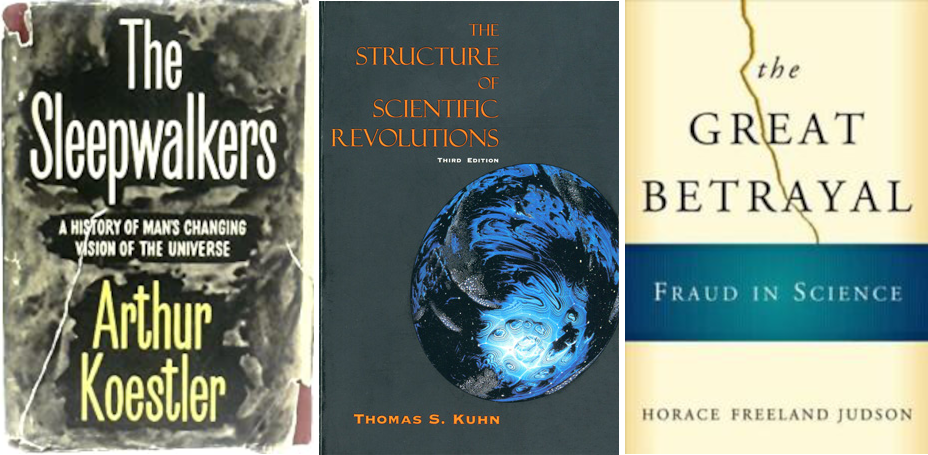

But then we get higher level ones like the Millikan Oil-Drop Experiment, which determines the charge of an electron. (And it is assumed that there is only one charge for all electrons.) But as it turns out, this oft-repeated experiment is very messy and requires selective reading to get “the correct result,” which by now is actually predetermined. In other words, there is only one correct result, and one has failed to perform the experiment correctly until one gets that correct result… which last I checked, was the complete reverse of what we’ve come to understand as scientific. Professor of Science Education, Mansoor Niaz, explains that “present-day undergraduate students do not consider the [Millikan] experiment either simple or beautiful but find it rather frustrating.”1 Science historian, Daniel P. Thurs, briefly debunks the myth “That the Scientific Method Accurately Reflects What Scientists Actually Do” in a great book called Newton’s Apple and Other Myths About Science out of Harvard University Press (2015). And Horace Freeland Judson confirms that the scientific method is a myth in his book The Great Betrayal: Fraud in Science (2004). As it happens, there is no standard scientific method.

Not even the idea of a “control” is always possible or even conclusive. Think about it! How can one account for all the variables? Surely there are circumstances that would demand multiple controls. And sometimes controls can introduce new biases. Science can’t always be done in a lab. And in some cases, science in a lab may have little to do with how things work outside the lab. And it all costs money. Moreover, as Judson points out, there are often incentives that drive certain results.

The other cornerstone stowree that Science tells about itself is directly linked to the method myth, and it’s the idea that scientific facts are arrived at through a gradual, cumulative and progressive process involving an ever-growing base of facts from which scientists deduce conclusions, which are further facts. But this too is untrue. If one spends time reading the history of science in books like Arthur Koestler’s The Sleepwalkers (1959) and Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), one discovers that science progresses (if that’s even the correct word) by fits and starts, by dead-end blind alleys and new discoveries generally mocked and rejected until they can no longer be denied… but that themselves wind up overturned later. So where exactly are the facts in all this? Hard to say exactly. (Though there do seem to be far more historical facts than scientific ones.)

Then there are all the science heroes: commonly accepted but false stories about folks like Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler and Darwin who suffered at the hands of religious authorities—those consummate enemies of Science. As it turns out, Copernicus, Galileo and Kepler were not tormented by the Church; indeed, they were encouraged by Church authorities. In fact, if it weren’t for the pursuit of theistic truth, folks like Copernicus would never have existed. Galileo did face an inquisitorial body, but not for his scientific claims. Instead, it was his direct belligerence and unhinged insults against higher-up clerics, including the Pope, that landed him in deep waters. And what’s more, when he did face that inquisition, it was in the most respectful manner one could imagine. There were no dark dungeons, no instruments of torture and no threats of burning at the stake. Galileo was placed under house arrest, in “a five-roomed flat in the Holy Office itself, overlooking St Peter’s and the Vatican gardens, with his own personal valet and Niccolini’s major domo to look after his food and wine.”2 In the end, he was let off with a slap on the wrist.

There’s plenty more on Galileo, but I’ll leave that for another day. My point here is that the heroes of science are fabrications. And the nature of their heroism—qualities like their stoicism and their irreverence for tradition and authority when it came to telling the Truth—actually has its roots in ancient sensibilities of heroism encoded in the Classical myths and biblical tales. They’ve simply been draped over new persons promoted by The Science in its war against Religion.

And even that war between religion and science is a myth, another story. Where does it come from? Well, that too will require a separate Barstool Bit. Suffice it to say for now that this particular stowree originated around the mid-1800s as scientists fought for recognition, remuneration and political authority—which at the time was entirely vested in the clerical class. Like Rodney Dangerfield, scientists of the time felt that no matter how hard they worked, they just couldn’t get any respect, and so they became more and more militant in their claims, promoting the idea that religion was the arch-enemy of Liberalism and progress. But the fact is that science emerged directly from religion and its efforts to understand Truth as the revelation of the nature of God. This was the project of folks like Copernicus, Kepler and Newton—to name just a few of the most famous.

Last week, I mentioned Kuhn’s point about textbook pedagogy in the sciences and how misleading such an approach to knowledge truly is. It abridges the actual history and messiness of the human endeavour to find the Truth and gives one the impression that science is just an accumulation of facts: “like reading the back of a paint can,” as I put it. What I’m getting at this week is that even textbooks tell stories of a sort, and that Science presents itself in the context of broader social stories. These days, those stories are about the progress of atheism as it battles religion, ignorance and superstition. None of this is true. This story is cover for the work that the institutions of science and New Atheists do to establish and maintain authority in every sphere of human activity. And thus The Science™ has emerged in the twenty-first century as the rhetorical framework of power: it’s the way authorities rationalise their diktats. In the good old days, monarchies received legitimacy from the Church. Kings and Queens were deemed to be the representatives of God on earth, and either the Pope or some other supreme holy office sanctioned that power. Now it’s The Science™ that tells us how to live. It validates government authority—sanctioning abridgements of human rights and establishing new dictatorships in what were just yesterday democratic nations.

In short, societies can’t function without storytelling. Power and authority are contingent on the stories we tell. And the real issue here (one analogy magazine keeps hammering away at) is that if a truly secular society is to continue, we need to be learning a lot of stories, not just the ones promoted by one book. And by “one book,” I mean to suggest a canon. The way the Bible is made of many books. Think of The Science as having a book, a collection of all the textbooks. In my analysis here we’ve been looking at the History Book. We need to inform ourselves along multiple lines with different perspectives, otherwise we’re falling into the same trap over and over again of saying, “This is the true canon. Don’t read that one over there. It’s false; while this one is true. Indeed, this one is the only true one.” This is the equivalent of saying, “My God is greater than yours. And His book is holy.” That sort of thinking… that relationship toward knowledge is the mainspring of ignorance and authoritarianism. Instead, we need to be reading those canons rejected by the predominant one, or we’re just playing into the hands of another authority, another religion.

Asa Boxer’s poetry has garnered several prizes and is included in various anthologies around the world. His books are The Mechanical Bird (Signal, 2007), Skullduggery (Signal, 2011), Friar Biard’s Primer to the New World (Frog Hollow Press, 2013), Etymologies (Anstruther Press, 2016), Field Notes from the Undead (Interludes Press, 2018), and The Narrow Cabinet: A Zombie Chronicle (Guernica, 2022). Boxer is also a founder of and editor at analogy magazine.

Numbers, Ronald L. and Kostas Kampourakis. Newton’s Apple and Other Myths About Science. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2015. p. 163.

Koestler, Arthur. The Sleepwalkers. New York, New York: Penguin Arkana, 1989. p. 498.