Why subscribe?

You will find no outrage in analogy magazine. Instead the aim here is to deliver mind-opening perspectives and a positive appeal to our better natures.

Analogy is an online magazine addressing the convergence of the arts and sciences.

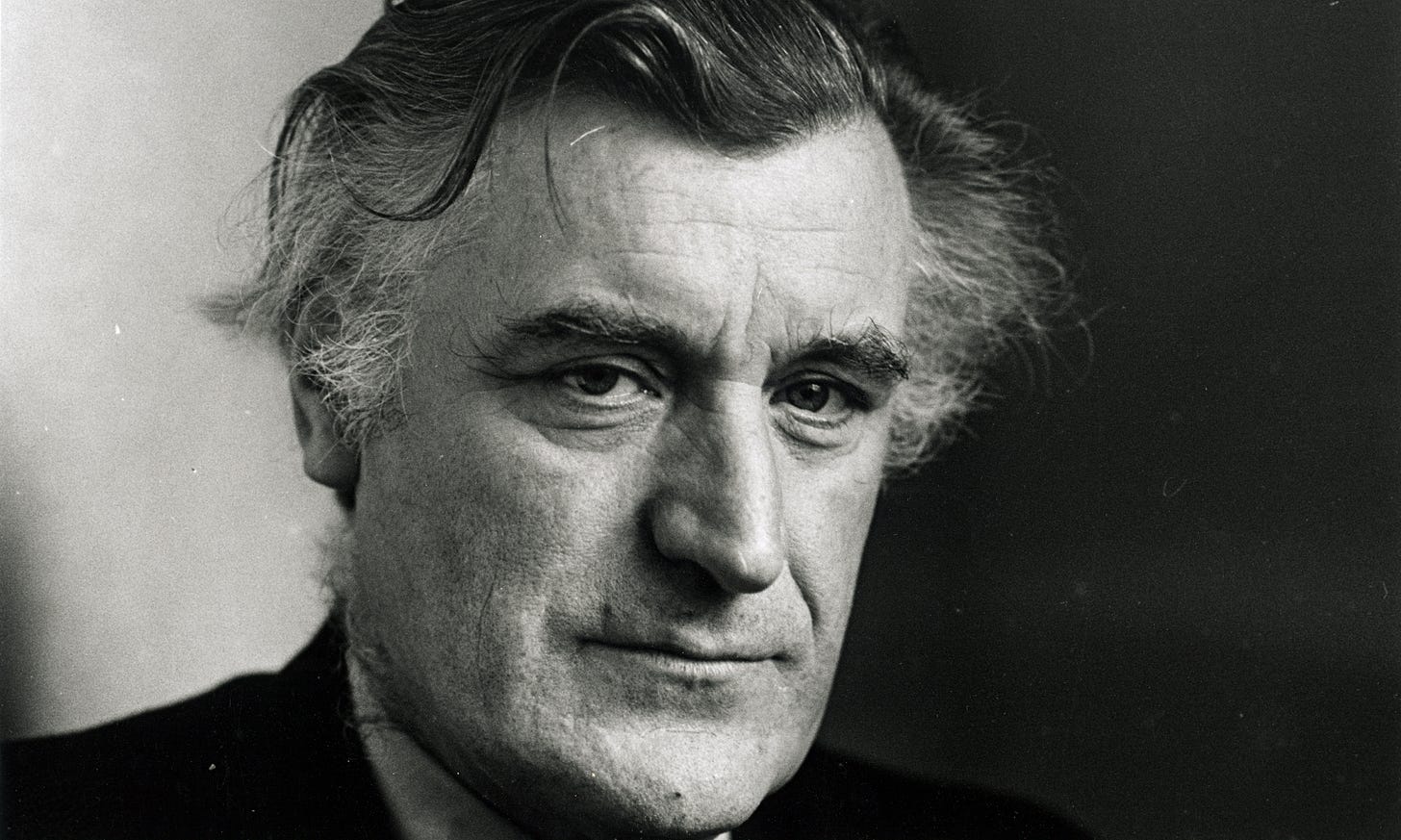

As former poet laureate of England, the late Ted Hughes, pointed out, we do not educate the imagination:

“A student has an imagination, we seem to suppose, much as he has a face, and nothing can be done about it.”

We propose that what emerges from training the imagination is the analogical mind, that subtle instrument that underwrites language itself and every insight and significant discovery ever hit upon by the most revered poets, philosophers, scientists and inventors in history.

Such a proposition is hardly controversial, but it is also largely unacknowledged and neglected. Both literary critics and scientists relegate analogy as a secondary concern when it comes to the material world of facts and practical physics. It is on this point that we beg to differ: analogy lies at the heart of all our cogitations and slips past our consciousness, shaping the paradigms and frameworks that inform our worldviews.

Hence we submit a second proposition: that generally speaking most of the analogies supporting any hypothesis or theory are incomplete and lead to necessarily incomplete frameworks. Moreover, well formulated analogies—known in poetics as conceits and in science as theories—come across with tremendous explanatory power, often giving the impression of dispensing capital-T Truth.

Analogy magazine is a response to this emergent orthodoxy and the frankly depressing notion that the science is settled and we have only the details to fill in.

Instead we promote a more inspiring view that we are still far from any sort of settled knowledge and that the pursuit of Truth remains wide open if only we would allow the imagination to learn the methods, pitfalls and potentials of the analogical mind.

Join the heretics

Be part of a community of people who share your interests in innovative and adventurous ways of thinking about the world.

Editor

Asa Boxer is the founder of and editor at analogy magazine. His poetry has garnered several prizes and is included in various anthologies around the world. His books are The Mechanical Bird (Signal, 2007), Skullduggery (Signal, 2011), Friar Biard’s Primer to the New World (Frog Hollow Press, 2013), Etymologies (Anstruther Press, 2016), Field Notes from the Undead (Interludes Press, 2018), and The Narrow Cabinet: A Zombie Chronicle (Guernica Editions, 2022).

SUBMISSIONS

You can reach us at analogymagazine@substack.com

Welcome to Analogy Magazine

The analogical mind is the root and radical of innovative creativity. Its insights inform all fields of human endeavour, from the most mundane situations requiring jury-rigging to the most sublime considerations of cosmic significance. But what exactly is analogy? How does it work? Why does it work? Where does it function consciously and where unconsciously? When does it succeed and when fail? How reliable is it? These are just some of the many questions that present themselves on the subject. And the goal of analogy magazine is to encourage exploration of all questions and propositions analogical.

That said, we are not so focused as to narrow our vision to subjects strictly analogical. It is not our intention that all articles address and relentlessly flog the subject, for analogy often operates best laterally: that is, we often stumble upon analogical insights while discussing subjects for their own sakes. By including works tangential to the topic in our pages, however, we hope to place them in a context that encourages considerations of their analogical processes and implications.

analogy is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The analogical mind is the faculty that perceives resemblances and makes unlikely connections. It is offset by the analytical faculty that perceives contrasts and draws distinctions. The one embraces, while the other discriminates. The two processes interact in that familiar compare-and-contrast dynamic we teach in our schooling programs. Balancing these two processes is the most fundamental intellectual skill, one that historically preceded the codification of deductive and inductive reasoning. Indeed we find the analogical and the analytical at play in Biblical and pre-Socratic reasoning—which is not to imply that Plato and Aristotle evolved beyond analogies, far from it. In fact, we may attribute the excitement of philosophical activity directly to analogical processes.

Consider for instance the Biblical Abraham and the fifth century B.C.E. Greek poet-philosopher Xenophanes of Colophon, who both observed that idols were not gods, but rather representations of or stand-ins for an abstract concept: they were both pointing to fundamental analogies, ones taken for granted, i.e. that certain carvings = gods. Imagine the thrill of the discovery! The analogical mind identified the equation and recruited the analytical mind as a wrecking ball. There it was as plain as one’s own nose staring at all humanity who remained blind to it until the analogical mind awakened, and with it, its analytical counterpart. The result was a transformation of consciousness. Similarly, when Plato suggested that perceived reality was but a shadow of true and perfect forms, he was making a similar point (analogically speaking) to that insight regarding idolatry.

When Pythagoras observed (prior to Plato) that geometry was this pure form, however, or when Plato decided to codify his forms in the design of a perfect Republic, or when Saint Paul began reifying analogies like the Church as the body, and Christ as the head—we observe another force at work: one I have come to call, the will to incorporation—essentially the instinct to close-off and lock-in a gain. This will to incorporation is both productive and counter-productive, and in any event represents a process as necessary to evolutionary progress as the one that brought about the closing off of a cell, without which no biological organism (or organ) would be possible. However, when considering things social and intellectual, this establishing of paradigms and closing them off, sets us right back to yet new forms of idol worship that hamper creative innovation because they confine the analogical-analytical interplay within their narrow parameters. It can also wind up clouding our perceptions and locking us into misguided doctrines (dogmas), sending us down centuries-long blind alleys. Such was the case for instance with our understanding of cosmology which was hampered for at least fifteen hundred years due to our adherence to Aristotelian and Ptolemaic worldviews.

Since analogy is as important as analysis, one might question, Why the emphasis on analogy? The answer is that we are well aware of analysis, but remain unaware of the role of analogy. In fact, the tendency in our society is to denigrate analogy even as we elevate analysis. Metaphors, we feel, are for poetry and other childish pursuits. The real work happens when we analyse the poem. This preference for analysis is moreover destructive, as it turns our focus too exclusively upon differences, to the point that resemblances slip past us; we don’t even notice that we employ them all the time, that indeed language itself is analogical (the words standing in for either objects or abstract notions) and that the analytical faculty would have nothing to work with without analogy.

Psychiatrist and neuroimaging researcher, Iain McGilchrist, has spoken to this cultural issue in his indispensable The Master and His Emissary (2009), discussing this subject in terms of left- and right-brain functions, and warning that the left brain (emissary) has usurped the master-function of the right brain, resulting in a culture that keeps sidelining its intuitive and creative dimension, including its talent for contextualising and peripheral awareness, in favour of narrowly focused, distinction-oriented, mechanistic and utility-centred aims. The right brain is the one that recognises and understands analogy, while the left provides the language to express it. This is where the trouble comes in according to McGilchrist: the right brain must engage the left to communicate, to act as its emissary. If however the left brain denigrates the right, we wind up with nothing more than a heap of meaningless machinery; indeed we wind up even perceiving ourselves in such a depressing manner.

Ted Hughes (1930-1998), the late poet laureate of England, addressed this trouble from an intuitive perspective—applying his finely tuned analogical mind—in a seminal essay written in the early 1970s entitled “Myth and Education.” He argued that we neglect the training of our imaginations at our peril, that the consequences of this negligence impacts us both psychologically and socially, putting us out of touch with our inner lives and vitality, and rendering us essentially heartless:

Sharpness, clarity and scope of the mental eye are all-important in our dealings with the outer world, and that is plenty. And if we were machines it would be enough. But the outer world is only one of the worlds we live in. For better or worse we have another, and that is the inner world of our bodies and everything pertaining. It is closer than the outer world, more decisive, and utterly different. So here are two worlds, which we have to live in simultaneously. And because they are intricately interdependent at every moment, we can’t ignore one and concentrate on the other without accidents. Probably fatal accidents.

In short analogy magazine emphasises analogy over analysis due to a sense of urgency. Our society is fractured, and our disciplines are atomised. We are mavens of discrimination, obsessed with how each of us is different. We are aware of a dizzying number of subatomic particles, their spins, their colours and flavours. But like the king’s men, we stand helpless before our Humpty Dumpty of a culture. Hughes remarks:

The inner world, separated from the outer world, is a place of demons. The outer world, separated from the inner world, is a place of meaningless objects and machines. The faculty that makes the human being out of these two worlds is called divine.

Upon analysis of this passage, we may distinguish the scientific, the psychological, and the divine. In each of these areas of human exploration and contemplation, analogy exhilarates with the thrill of confirmation, gracing the person at the centre of the enterprise with an intensely gratifying sense of inner cohesion and outer correlation, the sense that he has discovered a Truth that is at once universal and personally satisfying. Poets are all too familiar with this sense when elaborating a conceit. How all the pieces cohere hits one like a Eureka, feels like something discovered. Indeed poetry lovers are drawn to poetry for that very reason. But poets, because they work it from the inside, as it were, are privy to a secret about analogies: the fact that they work doesn’t make them true, certainly not in any final sense; indeed, sometimes they merely appear to work until one pulls at a thread and unravels the reasoning: what began as a matrix delivering the thrill of discovery winds up a heap of ash and disappointment. In short working with poems teaches us to work with paradigms, whether scientific or humanist.

When the orthodox New Atheist, Richard Dawkins, exhorts us to “swim around” in natural selection to fully appreciate it, the analogical mind retorts, Okay, but you too must swim around in the arguments of irreducible complexity to fully appreciate that perspective. Indeed natural selection is one of the world’s most magnificent and productive analogies: just as human beings have bred dogs and horses and pigeons; nature, through various selective pressures, has selected and bred all species. But this is only one poem, one conceit. In fact some poems include many conceits, and according to that analogy, we’re looking at only one unit of poetic imagination when we study natural selection. In other words, natural selection is incomplete: that is, only partly right. Same goes for special relativity and quantum mechanics. Sure. Let’s swim around in those conceits. But let’s not allow the will to incorporation shut down our ability to conceive of other frameworks.

The way Ted Hughes put it, we need to learn many stories, many myths; each may be viewed as a unit of imagination that once absorbed enters into “continual private meditation”:

they are also in continual private meditation, as it were, on their own implications. They are little factories of understanding. New revelations of meaning open out of their images and patterns continually, stirred into reach by our own growth and changing circumstances.

. . .

It does not matter, either, how old the stories are. Stories are old the way human biology is old. No matter how much they have produced in the past in the way of fruitful inspirations, they are never exhausted. . .There is little doubt that, if the world lasts, pretty soon someone will come along and understand the story as if for the first time. He will look back and see two thousand years of somnolent fumbling with the theme. Out of that, and the collision of other things, he will produce, very likely, something totally new and overwhelming, some whole new direction for human life.

If this can be said of a text, which is from a certain perspective, a field of data, how much more true must this be of the empirical world? Surely this is a more inspiring and vitalising perspective than the depressing notion that we have it all figured out, “that all the fundamental conceptions of truth have been found by science, and that the future has only the details of the picture to fill in,” as William James summarised the attitude in his 1895 lecture, “Is Life Worth Living?” His assessment of this take on the state of human knowledge was:

the slightest reflection on the real conditions will suffice to show how barbaric such notions are. They show such a lack of scientific imagination, that it is hard to see how one who is actively advancing any part of science can make a mistake so crude.

Hughes describes a person with no imagination as one “who simply cannot think what will happen if he does such and such a thing,” and must “work on principles, or orders, or by precedent.” Such a person “will always be marked by extreme rigidity, because he is after all moving in the dark”:

We all know such people, and we all recognize that they are dangerous, since if they have strong temperaments in other respects they end up by destroying their environment and everybody near them. The terrible thing is that they are the planners, and ruthless slaves to the plan — which substitutes for the faculty they do not possess. And they have the will of desperation: where others see alternative courses, they see only a gulf.

Sadly, this is the predicament of our world at present. To add confusion to the situation, it’s not that these “ruthless slaves to the plan” lack imagination, it’s that their imaginations are confined to one paradigm at the expense of all others: they’ve got their Grey’s Anatomy Colouring Book and there will be no colouring outside the lines. A stray pencil mark will drive a New Atheist—an orthodox disciple of The Science—to bristle and haemorrhage with expletives, abuses and mischaracterisations, betraying how thin his patina of rationalism. Analogy magazine hopes to bring greater balance to the cultural conversation and to inspire its readers with tantalising ideas that reveal new horizons and new potentials. As a part of that effort, one may expect of this magazine a measure of iconoclasm as we deploy the analytical wrecking ball to make way for daring, analogical insights. In that sense this venue remains a venue of heresies.

Those who’ve been following our magazine these past few years will know we began as The Secular Heretic. Migrating our content to Substack, we decided to make some changes, slough an old skin and emerge with a new light in our eyes. We are still secular in the sense that we promote pluralism, not in the sense of rejecting spiritual matters. And we remain heretics insofar as we go our own way, often offending predominant views. If a given paradigm is oppressive, we take up the gauntlet and offer offence. In that sense we offer far more resistance than those woke venues that purport to be the resistance (resistance to what exactly is unclear since they are the orthodoxy), and we offer far more scepticism than Skeptic magazine which refuses to turn a sceptical eye on New Atheist conceits, leaving one to wonder what partisan scepticism really has to offer.

For those new to the magazine, we encourage a perusal of our archives. For the most part we have avoided journalism and curated instead articles, poems and works of fiction that retain their interest value. We also hope you will be moved to add your thoughts to the comments sections. That is the point after all of using a venue like Substack. In due course, we hope you’ll reward our efforts by helping to support the magazine financially. Those interested in submitting works to us, please take a look at our guidelines on the About Us page.

In closing, I direct your attention to our latest offering, which we’ll be posting in the next couple of days. Jeffery Donaldson’s essay on metaphor “A Bridge is a Lie: How Science Does Metaphor,” will turn your thinking inside out and leave your perspective of reality entirely transformed. I read Donaldson’s book Missing Link: the Evolution of Metaphor and the Metaphor of Evolution some years back and returned to it recently to leverage its insights in a book of my own, parts of which I will be sharing with subscribers over the coming year. In Donaldson’s paper, I see the cornerstone of a new discipline in the humanities and the sciences, one we might call Analogical Science. Like all our best ideas, once understood, one is left to wonder how this was not obvious in the first place.

I hope that this welcome essay will act in some way to provide an even deeper understanding of what he’s after. Of course I come at the subject with my own canon of units of imagination in conversation with each other, and hope some productive discrepancies emerge between our formulations. In that spirit, I have been working on a companion piece to Donaldson’s, called “What is a Scientific Fact? Laying Bare the Heuristics”—which I hope grounds our critique of scientism with some practical examples of where popular science goes wrong with respect to its analogies.

As usual, you can expect some creative writing as well. A main departure in format however from The Secular Heretic is that we will no longer be publishing old school seasonal issues. From here on in, it’ll be one or two articles per month, occasionally accompanied by a creative piece or two.

I’ve also begun a weekly series called Barstool Bits. These are short reads which may address any number of things, from the metaphysical to the mundane. The idea is to present things in a simple and entertaining manner without getting too bogged down in references and complex, long-form arguments. When you subscribe, you’ll be automatically signed up for these, but if you’re email sensitive and prefer to just get the long reads and fewer emails, you can easily unsubscribe from Barstool Bits by hitting the Unsubscribe button on your email and toggling off the weekly series. If on the other hand, you like the short form, you can find them all collected together here.