The Language of Wisdom

Referring back to Neil deGrasse Tyson’s 2006 lecture at the Salk Institute, you’ll recall that he impugned the authors of a certain article in Nature discussing the 15% of the most elite and illustrious among scientists who still believed in God, saying the authors had “missed the story!” Correcting those poor, misguided writers, the reverend Dr. Tyson addressed his audience, declaring, “What that article should have said is, How come this number isn’t zero? That’s the story!”

But who’s missing the point? The more salient (and far more interesting) question following his survey of scientific heroes who all held spiritual beliefs would have been: How come it works? What is it about spiritual concerns that marks the most brilliant minds? What is it about their frame of mind that has helped bring about the most significant, consciousness-altering insights? That is the more interesting story to be sure! What is the source and wellspring of wisdom?

The answer is: in the analogical potential inherent to archetypal principles. Archetypes are ur-models, rudimentary and abstract: they are skeleton models, the ones that underly shifting temporal inflections—incarnations, as it were. Archetypes are the models that teach us how models work. Archetypes are, in that sense, the language of wisdom.

Proficiency with archetypes allows our minds to reach out and see their underlying patterns, analogically linking ideas and phenomena that to the analytical mind appear to be fragmented and unrelated. For instance, millenarianism, viewed analytically, was a superstitious belief common during the dark ages under the guidance of the Church. The analogical mind strips away the historical dimension, puts on x-ray goggles, as it were, and looks directly at the skeleton; thus it sees millenarianism, though it wears a new suit, at work again stoking climate alarmism.

Or to take an example that isn’t such a hot-button: it looks at the Big Bang and asks, Wait a minute! Isn’t that the same as the religious creation ex nihilo? Oh, a religious cleric came up with it? These points indicate a biased premise, a cause for scepticism. Or could it be that the Christian creation story is literally true? It’s certainly convenient in a way that ought to raise eyebrows.

Why are we seeing everything in quanta? Is it really all that remarkable that our quantising instruments have measured the outcomes of our experiments and established the objective reality of a quantised universe?

But then again, the power of archetypal thinking is that it retains a resonance with past, and present and even with future realities still unmanifest. The creation myth is in that sense truer: it accounts for more of the appearances. In asking the question, Where did the universe come from?—we must posit either an exploding singularity or a spontaneous emergence, like mushrooms in the darkness. If Time is a block already in existence, there lies the omniscience of the total system—the God Mind. Probability as a discovered attribute must melt away as an aberration if block Time is real. But still we haven’t answered the question: From whence the universe? By what agency? It begs the question.

Or to take another archetypal insight altogether: the historical confluence of scientific atomism (the obsession with particles) with social atomisation—I mean, the fragmentation of society along every line possible. . . This is surely more than coincidence, and in any case their coincidence begs examination. Why are we seeing everything in quanta? Is it really all that remarkable that our quantising instruments have measured the outcomes of our experiments and established the objective reality of a quantised universe?

We work with our models: our models are like appendages and tools. We participate in reality through their mediation (same as we do through our five senses) and then mistake the figurations they engender for the protean reality they were designed to navigate. We also make things happen to confirm the model’s agreement with reality. Indeed, if the commitment to the paradigm is codified and institutionalised, it becomes socially frowned upon to experience life outside the matrix. We begin hiding the data running contrary to our models even from ourselves.

What’s Psyche Got to Do with It?

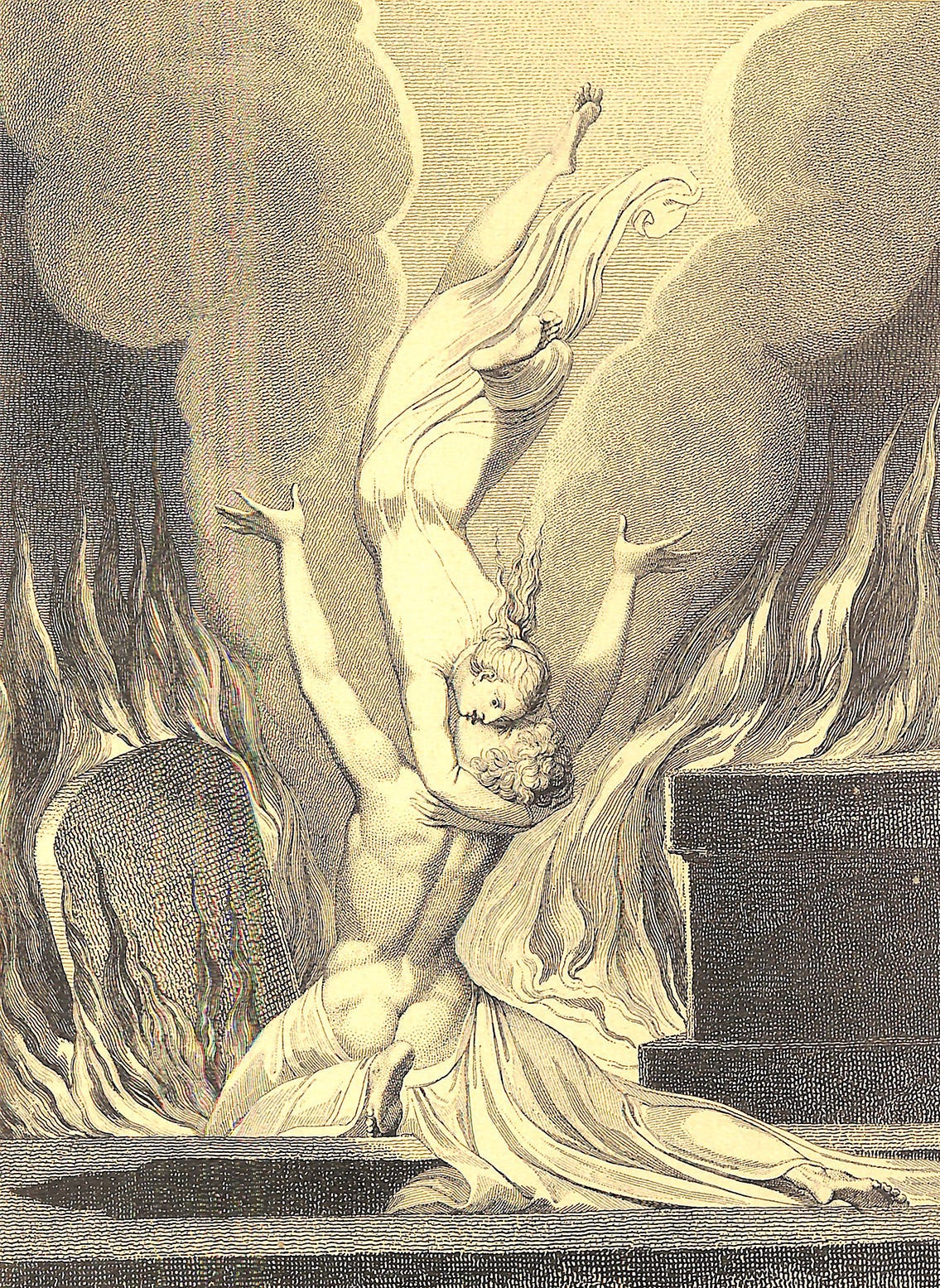

This burial of consciousness finds archetypal resonance with the tale of Psyche. Briefly, Psyche was a princess sacrificed at the hands of her community to a monster to appease the wrath of Aphrodite, whom Psyche had offended with her beauty. Her offence was that she obscured the True Aphrodite with her temporal Aphroditiness. In other words, Psyche became a kind of idol, obscuring the pure, archetypal form of Beauty. Or in still other words, she embodied the form only outwardly, neglecting the broader implications of inner Beauty.

As it happens, “the monster” to which she must be sacrificed is a non-existent fabulation of her community, a fact that becomes plain when she is released from her place of sacrifice by the most heavenly and princely creature, Love. . . whom she takes for her loving husband.

As we’ve seen before from the late poet laureate of England, Ted Hughes (1930-1998), the inner world cut off from the outer world is a place of demons. In other words our consciousness (Psyche) is sacrificed to irrational forces when it mistakes its own outer beauty for the one True Beauty within. Psyche grows shallow and superficial, concerned with quantities rather than qualities. And she requires rescuing by Aphrodite’s son, Love—no monster at all, a god in his own right, the archetype of analogy (the force that joins and marries things).

As the story goes, Psyche makes a pact with her mystery husband—she is unaware of his true identity—that she mustn’t attempt to peer upon his face and form. He comes to her at night and departs before daybreak. Psyche’s sisters however grow jealous and cajole her into finding out who he is. So one night, while he sleeps, she lights a lamp and holds it over him. Accidentally, she spills a drop of hot oil and burns him, waking him up. With a shriek of pain, he jumps to his heels tangled in the bedsheets, and then whoosh!—he opens his wings and departs in a flash. So Psyche’s downfall lies in her turning the vulgar light of analysis upon Love.

What does all this mean? The beauty of it is that I can’t tell you what it means. You’ve got to work it out for yourself. All I can provide are ways of reading, examples of how to engage the analogical mind. Unravelling the tale of Psyche is never exhausted because its relevance shifts with the times and the context. Today, the plight of Psyche seems to communicate an urgent message. And as mythos, it is certainly far more interesting, fulfilling and productive to engage with than the divisive worldview made of percentages, ledger books, and insurance-oriented safety ethics.

In any case, most perceive this archetypal discourse as wisdom because it is timeless. Archetypes address conditions that persist, resisting progress and technology. They even find expression in technologies: mythological gods like Vulcan in our war industry, Mercury in our electronics. They are the substance and language of our dreams, our inner world, and they find always-new expression in our changing worldviews and behaviours.

* * *

To help further clarify what I’m after, consider Ted Hughes’s book, Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being, in which Hughes argues that Shakespeare began his career working with two-dimensional archetypes and then, as his skills developed, learned to put flesh on them, working them up into realistic characters bristling with inner life. Indeed the endless potential for understanding human behaviour that we find encoded in Shakespeare is fundamentally anchored in this practice of his. We deem Shakespeare’s writing a receptacle of wisdom because it operates through archetypal, analogical modelling.

Let’s return to Tyson’s missed question: How come it works? What is it about spiritual seriousness that works to stimulate the greatest innovators of science? I propose it is mainly this analogical tendency to work often with archetypes; to have archetypal stories in continual private conversation with each other and with new stories or paradigms as they are absorbed. (Though this is not to discount the role played by hunches, luck, tedious, relentless experimentation, data collection and analysis.) Meanwhile it is likely that when spiritual types manage to resist closing themselves off from experiences of grace and revelation, they are far more likely to experience productive hunches and providential luck than those who reject such experiences. Would be interesting to find out how many of the finest minds in America covertly harbour a superstitious relationship to something they perhaps call “luck.” Luck is an acceptable experience in our society because it’s in the realms of the measurable, something that’ll become clear to humanity—so the reasoning goes—once we finally know everything as it truly is. There are of course plenty of theories of luck.

The Cult of the Holy %

All present knowledge is structured and tested according to probability and statistics. No article of thought is considered objective and scientifically true if not anchored in statistics, even if superficially. All media-news work consists in referencing percentages supplied by conventionally accepted sources. All present governance is rationalised in terms of statistics. Statistics are socially productive because they can easily sway opinion while also supporting just about any position. The entire covid scare was mediated by statistics, sloppy statistics and false projections—but it didn’t matter that the numbers were sloppy and false because the fear was framed in the right science language.

Our obedient relationship with languages of power is nothing new. Latin for instance performed that role of authority until a few hundred years ago—and still does in Catholic circles. . . and let’s not forget medical fields. In an important way, when it comes to power languages, it’s all hocuspocus to the public. All the trouble with a panic over what turned out in fact not to be a new Black Death lay in sorting out the relevant numbers from the irrelevant while allowing for a measure of noise in the data. This activity required some specialised skill, prompting interested parties to consult with data specialists to conduct their own evaluations and to critique the official messaging.

Frankly, even one unskilled in the field could tell the media weren’t providing the sorts of numbers one would expect, especially clear comparisons with past years’ hospitalisations and deaths. Nevertheless the public by and large trusted the specialists supplied to news-media to support government positions and actions. Why wouldn’t one trust the systems of dissemination when it came to something so urgent? To think that there may be something not-so-honest going on was considered camper-trailer “conspiracy theory” because questioning the holy % as dispensed by the Offices of officialdom was inconceivable.

In the end this is what the government and the public at large mean when they say Follow The Science: i.e. follow the guidance of the % dispensed by the institutions entrusted with public health and safety. It’s a pretty cautious position, one would expect. Except that historically speaking draconian moves abridging human rights and freedoms have never proven benign. Something else was going on, a power grab of immense significance for TheScience™, one that would instate its authority above all others like the Papal powers of yore that sanctioned coronations and state actions across the Catholic kingdoms.

The trouble is that % is not reliable. Nobody trusts the weather man, though oddly they still take his advice. How often do we think in an unanticipated downpour, But it wasn’t supposed to rain…? Supposed to? What a misguided perspective. . . to expect the phenomenon to fit the model! Among those sceptical of the weather forecast, one may encounter a mundane version of Pascal’s Wager (which is an argument for religious piety): better safe than sorry. The problems lie in (a) the malleability of the % method and (b) the cult of misanthropy that emerged from the probabilistic-statistical paradigm. The idea that humanity is its own worst enemy is no doubt seductive.

It’s a truism after all, easy for religious folk who believe in original sin to glom onto. Like the religion the present cult is rapidly replacing, there’s also a satisfying eschatology built into the very logic of its probabilistic and statistical models: the end of our limited resources; that is the End Days of the cult. For a while we worshipped the 𐠒 and now we worship the %. Once again the analogical mind is concerned with motifs that suggest we’ve been down this road before and we’re fooling ourselves to think this time it’s different because our paradigm finally really truly accounts for the really true appearances.

I can imagine some cynical folk wondering What’s wrong with that? I’d rather have this new religion over the stodgy old one no one really liked anyway. And I understand the sentiment, but a whole lot of babies are getting thrown out with the bathwater. The new religion relegates the inner life to a nuisance to be dealt with chemically. The inner life is after all just an epiphenomenon of chemical quanta, according to TheScience™. In that sense % is all the bad part of religion without the good. . . that is, it’s all the institutionalism and authority without the disciplines of the inner world. . . indeed without serious acknowledgement of the inner life, the heart life. The new religion is all structure and no content. It’s impersonal and dehumanising due to its necessarily large-scale, giantist view. And for the same reasons it is inherently anti-democratic, promoting a sort of beneficent tyranny of surveillance and compliance, all directed by the incorruptible %.

Sadly the ethic of the cult is an insurance and casino ethic: What can I get away with? What are the odds? Better to be the casino than the one trying his luck. Diversify your portfolio of assets. Stay safe. Take out life insurance. If evil befalls, it’s all replaceable.

This is not to say that the emotional world doesn’t assert itself in the face of tragedy, only that an insurance payout feels like a counterbalance to a material evil suffered. The cultural practice of insurance payouts conveys an artificially ethical world in which suffering finds reward. It promises an environment of stability in a world full of accidents. But it also casts an illusion of actual stability where none exists.

The question of identity became caught up in the cult of the % because finding one’s way to one’s true % in the cult became the only legitimate way to scientistic individuation. Gender, skin tone, ethnicity, race and sexual proclivities as concepts are perpetuated and even amplified by % studies because they are already conventional lines of discrimination with bodies of data attached.

This % perspective however leads to the cultivation of divisive contempt among segments of the population, who, using the % lens to appraise the world and their place in it, find themselves in common cause with folks foreign and unfamiliar who are either of the same %, or who are of the outcast % who have no %—and with whom they otherwise have little in common.

The contempt comes into play when competitive behaviour emerges in the context. Instead of fighting over who is fastest or more clever on an individual basis, the childish ground is ceded to who’s privileged and who’s oppressed according to the % game. The relation is no longer to a qualitative self that tests its skills against others, but rather to a quantitative self belonging to a % group and a class within the oppression-privilege % framework.

When people socialised that way speak, they do not speak for themselves, but on behalf of their % group. And they therefore regurgitate canned and group-approved speech, never learning to formulate original thoughts and speak for themselves. This is the principle by which people are relating, treating one another as % attractive machines with % potential to perform well in the machinery of consumerist systems.

Tragically, we forget how to love. (I could supply statistics and define love, but I hardly see the point.) Forgetting how to love is not insignificant. Love is not a vestigial pulmonary valve: it’s a primordial gateway out of the self, out of narcissism and toward being able to connect, empathise and participate in life.

The story of Psyche provides an apt archetype. She needs Love to save her from the monstrosity of a cut-off inner life, of a hollowed-out existence—one that affects her as much as her society. But to truly love requires imagination—in fact, requires an imagination free of the fetters of analysis.

In other words, humanity is presently being made to account for the appearances of the model; that is, we’re being made to conform to the model, so that we incarnate and become the perfect % model.

In present-day society the effort of imagination required to entertain love is becoming more and more difficult under the pressure produced by the social fixation upon the %. Like Psyche, we feel compelled to turn the analytical light upon our analogical yearnings, and so Love escapes, gets away from us. Such are the consequences when the analytical mind, the left brain completely occludes the inner world, locking the right brain away in a dark dungeon and throwing away the key.

The idol worship of the % cult is acute enough—and its way of looking at things has become common enough—that we live in societies bent on achieving % targets, and getting people to conform to the target numbers. In other words, humanity is presently being made to account for the appearances of the model; that is, we’re being made to conform to the model, so that we incarnate and become the perfect % model.

We are now therefore enslaved to the probabilistic-stastistical model, in servitude to its empty machinery, guided by a ledger-book ethics and afraid of the bogeymen of the inner world, our emotional lives, and those large-scale bogeymen too that assert themselves under the guise of some % chance of disaster that threatens to disrupt the bouncy-castle, bubble-tent life waited upon by those angels of consumerism, Santa and the Tooth Fairy (guarded by the insurance adjuster behind the fenced-off area). Both private and public spheres are now mediated entirely by this paradigm.

And in case I haven’t been clear, this state of affairs, our worship at the shrine of the Holy % is bad. It’s unhealthy both physically and psychologically, and it’s politically abusive and anti-democratic; it sets humanity against itself, promoting fear and self-loathing; both we ourselves as well as our colleagues and neighbours we view as infectious bags of disease and “anthropogenic” planet destroyers driving us all (by our selfish %) toward a black hole of inevitable gravity inherent to and determined by the terms of our % measures. To correct our filthy selves, we must conform to the tools of purity and fit ourselves to the models of purity. To put it in overtly analogical terms, we are victims of Frankenstein’s monster, at the mercy of Hal 9000. The matrix of this system is no longer there to serve us. No. We must now serve it.

Our best response (as far as I can see) is to prioritise languages other than the statistical-probabilistic one wherever possible. It is making us neurotic, unhappy personally, and dysfunctional socially. Nothing could be more urgent at this moment in our history than the recognition of this unfortunate (inner-world emptying) relationship we are suffering through at the hands of the presently dominant paradigm.

The analogical mind generates a conceit comparing past religion and its way of doing things with the present paradigm and its way of doing things. It finds correlations so close, it questions what essentially has changed, not superficially speaking, but in truth. What it discovers, using the language of wisdom is that the new paradigm is in every way like a late phase religion, fully engaged in the will to incorporate, steeped in its dogma and looking to shape the world according to the diktats of its institutions.

What has changed is that the new religion has no place for the inner world (arguably this is what happened to the old religion), and is therefore beset by irrational forces playing themselves out through the new paradigm. Since the new paradigm has branded itself the pinnacle of rationality, spotting the irrational presents an extra barrier to seeing it for what it is, a cult. In short the same ancient drives and fears are with us, only now they are being projected as “real” bogeymen with % attached to them as opposed to those silly beliefs of yore that lacked the final authority of the %—but for some reason seemed just as real.

To heal ourselves we must reconnect with our inner forces and reclaim our imaginative ability to truly love. The language of wisdom informs us that a life of love is preferable to a life of fear, and ideologies and paradigms that promote fear ought to be viewed with extreme scepticism because fear is the language of the irrational, while love is the language of the right brain—that faculty which shines the light of intelligence upon the greater whole and points to its unities and correlatives.

Love offers the way toward harmony as the analytical tools are subordinated to the user of the tool, rather than the reverse logic of the left brain where the person is subordinated to the tool (or model) and must be made to conform to it.

If love is being shunted aside, surely that ought to be a red flag. We should be looking to restore our society to one that promotes an ethic of Love rather than one that fosters a focus on societal hate (which is where the % points).

Happily there’s a Love instinct (indeed an archetype) that can’t be entirely smothered by matchmaking algorithms, and most folks know deep down that something is amiss with that whole way of looking at things. The problem now is how to find room for its expression in a world that is so much more than a %, but that has no language, no archetypes, no mythoi with which to express it or with which to manage its various inner forces.

Asa Boxer’s poetry has garnered several prizes and is included in various anthologies around the world. His books are The Mechanical Bird (Signal, 2007), Skullduggery (Signal, 2011), Friar Biard’s Primer to the New World (Frog Hollow Press, 2013), Etymologies (Anstruther Press, 2016), Field Notes from the Undead (Interludes Press, 2018), and The Narrow Cabinet: A Zombie Chronicle (Guernica, 2022). Boxer is also a founder of and editor at analogy magazine.

Love has become so fickle these days that it feels like little more than a gesture of conditional acceptance into a cult: you get "love" so long as you think, say, and do as we do. Decades-long friendships and family bonds were severed on those terms on a mass scale during the covid scam.

Wonderful essay, by the way. It's got me wondering how we might figure out how to love again in a society that hates itself and wants to die.

Wowzers.

I bought a ribeye for dinner, but I can set it aside because this mega-essay is more than sufficiently juicy and nutritious. Tons to say here, but to be super brief:

If you want to lay barebear what statistics did to actual causality and connection with Reality, enjoy the first several chapters of ‘The Book of Why’ by Judea Pearl —absolutely gold.

Final observation: I think we should all start referring to him as the “Reverend Dr. Tyson” from here on out. Savage :-)