Welcome to Barstool Bits, a weekly short column meant to supplement the long-form essays that appear only two or three times a month from analogy magazine proper. You can opt out of Barstool Bits by clicking on Unsubscribe at the bottom of your email and toggling off this series. If, on the other hand, you’d like to read past Bits, click here.

Over the past couple of months I have gone about complicating canonical science myths by introducing some apocrypha and pointing to some irrational bits that don’t jive with the claim that TheScience™ is all about honest men and women in search of Truth, who were and are prepared to risk it all to tell the world of their extraordinary findings.

Sadly I’ve barely scratched the surface where fraud is concerned. Nary a hero can be salvaged: not Newton, not Darwin, not Pasteur, not Freud, not Eddington, not Millikan to name the most famous. From the latter end of the twentieth century and well into the start of the twenty-first—at the dawn of the desecularisation of science and the emergence of its pod-person alter ego TheScience™—a literature has been emerging uncovering a culture of scientific fraud and scientism. Horace Freeland Judson locates a culture of fraud squarely within a larger framework of institutions, exposing at the start of his book The Great Betrayal: Fraud in Science all the fraudulence characterising every institution of the twentieth century from banking to corporate to governmental to clerical, our systems are shot through. Pick at the marble facade of any venerable pillar and you’ll find dry rot at the core.

When it comes to science in particular a great deal hinges on the explosion of funding that went to the sciences during WWII and immediately in its wake. Once science was industrialised for war and technology, once it became corporatised and directed by narrow interests, the whole spirit of secular science was lost. The informal mentorships with notable persons of science were replaced with impersonal, textbook-guided training programs followed by formal mentorships. Inadvertent discoveries in one field that serve another have become less likely due to proprietary work being hidden behind corporate screens. Breakthroughs that might upset built in obsolescence are suppressed.

Impenetrable jargons proliferate. Some, like Thomas Kuhn, generously perceive this vocabulary as a natural consequence of specialisation. But like the Latin of the Catholic Church, specialised vocabulary has the effect of discouraging outsiders from weighing in, or from feeling like it’s the business of anyone other than a special clerical class. Potentially worse has been the fall off of funding for science after the bullish Boomer boom, exerting more pressure on scientists to conform to the demands of funding agencies and to inflate the success of their findings.

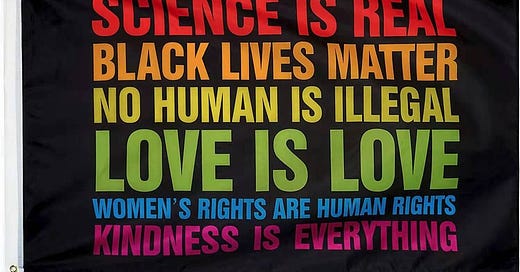

The myth busting and science debunking I’ve been doing over the past couple of months demonstrates how false twenty-first century notions of science have come to be. It wasn’t always the case that the public was enjoined to Follow The Science. This cultish manner of thinking is brand new and a result of propaganda emerging from the corporate sector, government agencies and the climate lobby. Entirely unscientific notions like settled science and scientific consensus have been propagated by popular science magazines, documentaries and serialised television (and video) media. . . and of course social media and recent government policy and collusion with big tech and the news media bringing to bear social pressures, censorship and the false “fact checking” initiatives that sprung up in the wake of the covid scare, but had already been developed and deployed in the climate information war.

Of course scientism could never have gained traction had our science education been an honest one. Were our heads not filled with all manner of myths, heroes and science idols; had the humanities been taught to science majors (and all university students for that matter); were scientists trained on primary sources rather than given textbook versions of their fields. . . no government nor any population could have been seduced into this counter-science, counter-secular, counter-democratic backsliding.

Worth pointing out that the Victorian founders of scientism did not perceive science in such a thoroughly distorted way since they themselves were pushing back against the elitism and authoritarianism of their day. Even Thomas Huxley—who (as noted elsewhere) was especially guilty of promoting Science as the new religion and Reformation, indeed as the inevitable and final revelation begun by the Protestant movement—maintained that what he was fighting against were those barbarous folks who held the following conviction:

that authority is the soundest basis of belief; that merit attaches to a readiness to believe; that the doubting disposition is a bad one, and scepticism a sin; that when good authority has pronounced what is to be believed, and faith has accepted it, reason has no further duty.1

So an honest science education is a key corrective measure. But the deeper argument I’m after is that the cultural drift in the direction of scientism would never have gained such devastating influence had our culture trained the analogical mind and strengthened right-brain functions. Had we not allowed the humanities to be gutted; had we filled our inner worlds rather than hollowed them out; had we promoted more interest in qualities and less in quantities—we would not be facing this horrifying period of millenarian panic and a world populated by meaningless machinery.

Asa Boxer’s poetry has garnered several prizes and is included in various anthologies around the world. His books are The Mechanical Bird (Signal, 2007), Skullduggery (Signal, 2011), Friar Biard’s Primer to the New World (Frog Hollow Press, 2013), Etymologies(Anstruther Press, 2016), Field Notes from the Undead (Interludes Press, 2018), and The Narrow Cabinet: A Zombie Chronicle (Guernica, 2022). Boxer is also a founder of and editor at analogy magazine.

See Barton, Ruth. The X Club: Power and Authority in Victorian Science. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2018. p. 377.

The "explosion of funding" you describe that went to the sciences before and during WWII is an essential point. My research into the origins of globalism shows that the new American millionaire monopolists who flourished in the early twentieth century established multinational philanthropies, hiring corporate missionaries to propagate the "application of modern science" in education, medicine, agriculture, industry, and so on, both domestically and to benighted foreign countries. The monopolists' crusade was to shape the future of the international financial system in order to consolidate their power and control through education and missionary work. They wanted to revolutionize the world, and they succeeded, so much so that they've ended up retarding it for generations to come, as you illustrate so well in this latest bit.

I like Boxer’s called out of right brain thinking. Iain McGilchrist has an awful lot to say on this point.